I have already presented my views on the relative patent risk of WebM, based on my preliminary analysis of the source code and some of the comment of Jason Garett-Glaser (Dark Shikari), author of the famous (and probably, unparalleled from the quality point of view) x264 encoder. The recent Google announcement, related to the intention to drop the patented H264 video support from Chrome and Chromium (with the implication that it will be probably dropped from other Google properties as well) raised substantial noise, starting with an Ars Technica analysis that claims that the decision is a step back for openness. There is an abundance of comments from many other observers, that mostly revolve around five separate ideas: that WebM is inferior, and thus it should not be promoted as an alternative, that WebM is a patent risk given the many H264 patents that may be infringed by it, that WebM is not open enough, that H264 is not so encumbered as not to be usable with free software (or not so costly for end users) and that Google provides no protection against other potential infringing patents. I will try, as much as possible, to provide some objective points to at least provide a more consistent baseline for discussion. This is not intended to say that WebM is sufficient for the success of HTML5 video tag – I believe that Christian Kaiser, VP of technology at Netflix, wrote eloquently about the subject here.

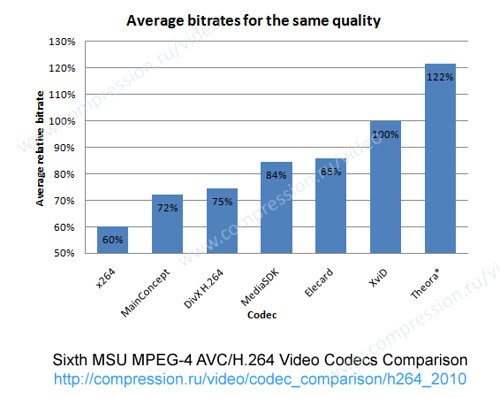

Quality: quality seems to be one the main criticism of WebM, and my previous post has been used several times to demonstrate that it does employ sub-par techniques (while my intention was to demonstrate that some design decisions were made to avoid existing patents, go figure). The relative roughness of most encoders, the limited time on the markete of the open source implementation led many to believe that WebM is more in the league with Theora (that is, not very good) and not in that of H264. The reality is that encoders are as important as the standard itself for evaluating quality, and this of course means that comparing WebM with the very best encoder in the market (x264) would probably not give much an indication on WebM itself. In fact, a very good comparison by the Moscow state university’s Graphics and media lab performed a very thorough evaluation of several encoders, and an interesting result is this:

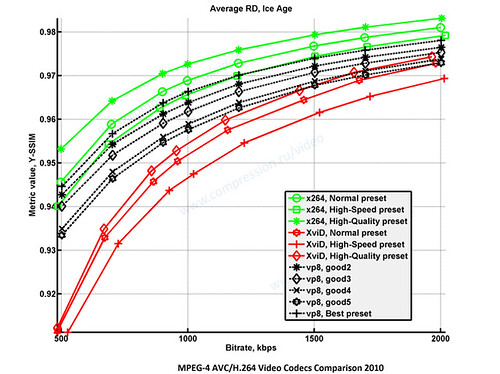

(source: http://compression.graphicon.ru/video/codec_comparison/h264_2010/#Video_Codecs) where it is evident that there are major variations even among same-technology encoders, like Elecard, MainConcept and x264. And WebM? Our russian friends extended their analysis to it as well:

What this graph shows is the relative quality, measured using a sensible measure (not PSNR, that values blurriness more than data…) of various encoding done with different presets, with x264, WebM (here called VP8) and Xvid. It shows that WebM is slightly inferior to x264, that is it requires longer encoding times to reach the “normal” settings of x264; and it shows that it already beats by a wide margin xvid, one of the most widely used codecs. Considering that most H264 players are limited to the “baseline” H264 profile, the end result is that – especially with the maturing of command line tools (and the emergence of third party encoders, like Sorenson) we can safely say that WebM is or can be on the same quality level of H264.

WebM is a patent risk: I already wrote in my past article that it is clear that most design decisions in the original On2 encoder and decoder were made to avoid preexisting patents; curiously, most commenters used this to demonstrate that WebM is technically inferior, while highlighting the potential risk anyway. By going through the H264 “essential patent list”, however, I found that in the US (that has the highest number of covered patents) there are 164 non-expired patents, of which 31 specific to H264 advanced deblocking (not used in WebM), 34 related to CABAC/CAVAC not used in WebM, 16 on the specific bytecode stream syntax (substituted with Matroska), 45 specific to AVC. The remaining ones are (to a cursory reading) not overlapping with WebM specific technologies, at least as they are implemented in the libvpx library as released by Google (there is no guarantee that patented technologies are not added to external, third party implementations). Of course there may be patent claims on Matroska, or any other part of the encoding/decoding pair, but probably not from MPEG-LA.

WebM is not open enough: Dark Shikari commented, with some humor, of the poor state of the WebM standard: basically, the source code itself. This is not so unusual in the video coding world, with many pre-standards basically described through their code implementations. If you follow the history of ISO MPEG standards for video coding you will find many submissions based on a few peer-reviewed articles, source code and a short word document describing what it does; this is then replaced by well written (well, most of the time) documents detailing every and all the nooks and crannies of the standard itself. No such thing is available for WebM, and this is certainly a difficulty; on the other hand (and having been part, for a few years, of the italian ISO JTC1 committee) I can certainly say that it is not such a big hurdle; many technical standards are implemented even before ratification and “structuring”, and if the discussion forum is open there is certainly enough space for finding any contradictions or problems. On the other hand, the evolution of WebM is strictly in the hand of Google, and in this sense it is true that the standard is not “open” in the sense that there is a third party entity that manages its evolution.

H264 is not so encumbered-and is free anyway: Ah, the beauty of people reading only the parts that they like from licensing arrangements. H264 playback is free only for non-commercial use (whatever it is) of video that is web-distributed and freely accessible. Period. It is true that the licensing fees are not so high, but they are incompatible with free software, because the license is not transferable, because it depends on field of use, and in general cannot be sensibly applied to most licenses. The fact that x264 is GPL licenses does not mean much: the author has simply decided to ignore any patent claim, and implement whatever he likes (with incredibly good results, by the way). This does not means that suddenly you can start using H264 without thinking about patents.

Google provides no protection against other potential infringing patents: that’s true. Terrible, isn’t it? But, if you go looking at the uber-powerful MPEG-LA that gives you a license for the essential H264 patents, you will find the following text: “Q: Are all AVC essential patents included? A: No assurance is or can be made that the License includes every essential patent. The purpose of the License is to offer a convenient licensing alternative to everyone on the same terms and to include as much essential intellectual property as possible for their convenience. Participation in the License is voluntary on the part of essential patent holders, however.” So, if someone claims that you infringe on its patent, claiming that you licensed it from MPEG-LA is not a defense. And, just to provide an example, in the Microsoft vs. Alcatel/Lucent case, MS had to fight quite a long time to have the claim dismissed (after an initial 1.52B$ damages decision). In a previous effort for creating an open video codec by Sun Microsystem, Sun similarly did not introduce a patent indemnification clause in it – in fact, in one of the OMV presentations this text was included: “While we are encouraged by our findings so far, the investigation continues and Sun and OMC cannot make any representations regarding encumbrances or the validity or invalidity of any patent claims or other intellectual property rights claims a third party may assert in connection with any OMC project or work product.”

So, after all this text, I think that there may be some more complexity behind Google’s decision to drop H264 than “we want to kill Apple”, as some commenters seem to think – and the final line is: software patents are adding a degree of complexity to the ICT world that is becoming, in my humble opinion, damaging in too many ways – not only in terms of uncertainty, but adding a great friction in the capability of companies and researchers to bring innovation to the market. Something that, curiously, patent promoters describe as their first motivation.

#1 by antimatter15 - February 2nd, 2011 at 00:01

Great article. But chromium never had support for h.264 or mp3 for that matter

#2 by Greg - February 2nd, 2011 at 08:14

Stop spoiling it for everyone. The “Google is sticking it to Apple” story is much more entertaining than the prosaic facts.

#3 by El Lizardo - February 2nd, 2011 at 08:30

Sincere question – how will WebM improve over time (in terms of quality and feature set) without infringing on all those patents?

#4 by cdaffara - February 2nd, 2011 at 09:16

That’s a very good question; a problem of the current patent environment is that there are not only the H264 patents to avoid, but an entire minefield that is extremely hard

to travel unscathed. My own belief is that improvements are possible in two areas: preprocessing of video material to make it easier to process (things like film grain separation)

and iterative encoding that used non-psycho-visual measures to direct bit allocation. At the moment WebM is roughly equivalentto a good H264 encoder, and in the lower league of x264 (that

is absolutely the best in the market). Overall, it is good enough to be competitive, quality wise; the biggest problem is encoding speed, that is abysmal (well, probably not that bad, but certainly too

slow). On that I believe that it is possible to improve substantially without infringing patents.

#5 by cdaffara - February 2nd, 2011 at 09:16

Ah! But I am trying to spoil fun for everyone! Despicable me!

#6 by cdaffara - February 2nd, 2011 at 09:17

Yes – it is Chrome that embeds native mp3 and H264 support, thanks to a license obtained from MPEGLA.

#7 by Andy - February 2nd, 2011 at 18:29

Let’s hope John Gruber (of Daring Fireball) reads this!

#8 by Arturo - February 2nd, 2011 at 20:41

Quoting: Considering that most H264 players are limited to the “baseline” H264 profile, [...] we can safely say that WebM is or can be on the same quality level of H264.

But isn’t the graph saying the opposite, with VP8 *best* on par with x264 *worst*? Am i misinterpreting the graph?

Or is it assumed that the bitrates used for HTML5 video will be around 500kbps, where VP8-best matches x264-normal?

#9 by Tim F. - February 3rd, 2011 at 03:15

The “mostly just baseline” myth doesn’t work anymore — the vast majority of smartphones made over the last few years easily support main profile up to 720p at 30fps.

#10 by Jason IANAL - February 3rd, 2011 at 03:27

The advantage of MPEG-LA over Google is that patent holders have a choice to join a patent pool that would advance their mutual interests.

If a patent holder knows about a patent pool, but chooses not to inform the pool of their patent, it could be found as an indication that they waive their right to enforce their patent (e.g. Qualcomm v. Broadcom (2008)).

The members of a patent pool would also have a common interest in protecting their patents against a patent holder outside the pool.

Therefore, the patent risk is lower with H.264 than VP8.

#11 by cdaffara - February 3rd, 2011 at 08:36

The problem may be more complex than that. In the Alcatel/MS trial, the existence of additional patents was not found to be an automatic waiver – a fact that is also part of Qualcomm vs Broadcom (the waiver was decided because “when a witness for Qualcomm in a patent dispute admitted that she had received e-mails from a mailing list (called the “avc_ce” list) which was evidence of Qualcomm’s participation in a standards setting body (called “JVT,” on the “H.2264″ standard) before a specific point in time. In the Court’s words, Qualcomm’s assertion that it had not participated in the JVT was “vital” to its success in defeating Broadcom’s waiver argument” ( http://allaboutinformation.ca/2008/01/09/more-on-qualcomm-v-broadcom-sanctions-case/ )

The problem in Qualcomm/Broadcom was that a Broadcom employee was participating in the mailing list debating the very same standard, and thus falls within ISO rules; if such a participation was not to be proved, the waiver would have been not granted.

In fact, MPEGLA does not automatically guarantee that licensing a pool provides guarantee against any other patent claim – a company may be part of the patent pool for one standard, and not part for another, and if it finds that it infringes on its IPR is perfectly in his rights to go through a legal suit or ask compensation.

Also, cross-agreements between patent holders in a pool may prevent legal retaliation against an outside member claiming patent infringement.

So, all given, I would still claim that, until MPEGLA finds an infringing patent, VP8 is *at least* on a par with H264, and if no other patent is found, probably better.

#12 by cdaffara - February 3rd, 2011 at 08:39

Maybe – but most encoding companies still claim otherwise:

http://zencoder.com/encoder-blog/2010/09/30/how-to-encode-video-for-mobile-use/

The advanced smartphone profile still applies only to iphone4, ipad and Apple TV; for the advanced profile, “Nexus One, Droid, maybe others. (YMMV on these, though. Some users report trouble with 720p video.)” (something that I can confirm). This hardly makes for “the majority of smartphones made over the last few years”, even excluding the largest installed base, Nokia (that would not know an advanced profile if it bite it in the cpu).

#13 by Arturo - February 3rd, 2011 at 12:54

Even conceding that H.264 video will be limited to the baseline profile, why assume that the situation with WebM will be different?

BTW, my prediction is that serious video sites will have both H.264 ‘advanced’ video and WebM as a fallback. A very good addition to the HTML5 video tag would be automatic fallback, we don’t want to go back to ugly User-Agent sniffing.

#14 by Dave - February 3rd, 2011 at 14:10

Note that the H.264 encoders tested in the Russian comparison were encoded at High Profile (as indeed are most comparisons you see).

Not only does this not play on the vast majority of mobile devices with hardware support, which are restricted to Baseline, but even the most recent iPhone and iPad are limited to the Main Profile. It’s actually quite difficult to find videos encoded in this middle setting, most people jump straight from Baseline to High as there is little benefit to doing so. You may think that recent iPhone 4 and iPad support is enough, but if the next version (or the one after that) does actually support High Profile, are you really going to supply 3 different encodes just for iDevices alone?

#15 by Razvan Vilt - February 3rd, 2011 at 16:48

There is one more argument that everyone is missing:

All streamable content out there is either MPEG2 or H.264. Bandwidth is not a problem anymore. Can anyone explain to me why I have to re-encode in realtime 120 DVB streams to WebM if I want to offer my customers access to all their TV stations over HTTP when they are away from home? Using H.264, I only have to re-encode a few of the streams from MPEG2 to H.264 and simply stream the raw transport streams from the other ones.

Until someone can provide an appliance that re-encodes H.264 1080p50i content to WebM in real-time for up to $500 per stream, I think that it’s ridiculous to assume that we can move to WebM.

#16 by Todd - February 5th, 2011 at 13:00

Regarding possible patent infringements on H.264, a common argument is that because H.264 has such wide adoption at this point that any party that was going to claim infringement and compensation would have done so by now. Basically, if you are going to be a patent troll, you wait until there has been enough adoption to make your payday as big as possible. Because WebM had very little adoption, patent holders have not been motivated to seek compensation, but if it becomes a standard as Google seems to be promoting, the trolls will come out of the woodwork.

The fact that there is a patent pool with quite few members and that H.264 is in wide use at least makes it seem less likely that patent infringement will arise at this point. Obviously it is still possible, but it it seems much more likely to happen with WebM.