Archive for February 24th, 2009

On business models and their relevance

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on February 24th, 2009

Matthew Aslett has a fantastic summary post that provides a sort of synthesis of some of the previous debates on what is an OSS business model, and how this model impacts the performance of a company; along with the usual sensible comments. There are a few points that I would like to make:

- It is probably true that a pure service-based company is less interesting for VC looking for an equity investment (by service-based I mean: “Product specialists: companies that created, or maintain a specific software project, and use a pure FLOSS license to distribute it. The main revenues are provided from services like training and consulting” from the FLOSSMETRICS guide). Every service-based model of this kind is limited by the high percentage of non-repeatable work that should be done by humans; so the profit margins are lower than those of the average software industry or of other OSS models. On the other hand, unconstrained distribution (facilitated by the clear, unambiguous model and single license) in many cases compensates for this lower margin by increasing the effectiveness of marketing messages.

- Tarus Balog notes: “For those companies trying to make billions of dollars on software quickly… the only way to do that in today’s market is with the hybrid model where much of the revenue comes from closed software licenses.” That’s right- at the moment this seems the only possible road to a 1B$ company. What I am not convinced of is that this is in itself such a significant goal; after all, the importance of being “big” is related to the fact that bigger companies have the capability of creating more complex solutions, or to be capable of servicing customers across the globe. But in OSS, complex solutions can be created by engineering several separate components, reducing the need of a larger entity creating things from scratch; and cooperation between companies in different geographical areas may provide a reasonable offering with a much smaller overhead (the bigger the company, the less is spent in real R&D and support). A smaller (but not small) company may still be able to provide excellent quality and stability, with a more efficient process that translates into more value-for-dollar for the customer.

- I believe that in the long term the market equilibrium will be based on a set of service-based companies (providing high specialization) and development consortia (providing core economies of scale). After all, there is a strong economic incentive to move development outside of companies and in reduce coding effort through reuse. Here is an example from the Nokia Maemo platform:

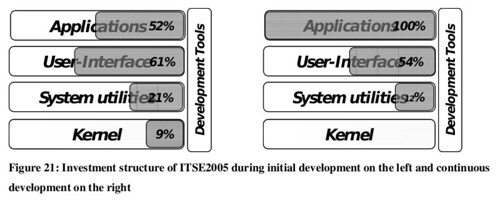

In this slide from Erkko Anttila’s thesis (more data in this previous post) it is possible to see how development effort (and cost) was shifted from the beginning of the project to the end. The real value comes from being able to concentrate on differentiating, user-centered applications – those can be still developed in a closed way, if the company believes that this gives them greater value; but the infrastructure and the 80% of non-differentiating software expenditure can be delivered at a much lower price point if developed in a shared way.

In this slide from Erkko Anttila’s thesis (more data in this previous post) it is possible to see how development effort (and cost) was shifted from the beginning of the project to the end. The real value comes from being able to concentrate on differentiating, user-centered applications – those can be still developed in a closed way, if the company believes that this gives them greater value; but the infrastructure and the 80% of non-differentiating software expenditure can be delivered at a much lower price point if developed in a shared way. - Development consortia (like the Eclipse consortium) can act as a liasion/clearing office for external contributions, simplifying the process of contribution from companies. The combination of visibility and clear contribution processes can help companies in the shift from “shy participants” that prefer to have individual developers commit changes to projects (thus relieving the company from any liability, but still reaping the advantages of participation) to contribution and championing.

The dynamics of OSS adoption – 1

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on February 24th, 2009

There are many different mechanisms behind OSS adoption, and understanding the differences makes it easier to help companies in using them efficiently – after all, word of mouth may be sufficient to get visibility, but it may be not enough to guarantee adoption, and then converting this adoption into paid services.

In fact, monetization may require a large number of “adopters” to get a small percentage of “paid users” – in many domains, only 0.05% of adopters pays for services, a percentage that we call “unconstrained monetization percentage” or UMP to make it sound more academic.

While it is true that the incremental cost for the OSS company of having a new adopter is zero (or extremely small), the increased adopters base also increments the probability that the community or some competitor will start to address the same monetization path, thus further reducing the UMP. So, to take the example of MySQL, instead of asking services or training to Sun, an adopter may opt for a local consulting firm that effectively leverage the free availability of the code and ancillary material to create a competitive entry.

Of course, the business model adopted by the OSS firm also has a positive or negative effect on the growth process in the number of adopters; this especially affects firms offering what we called “split OSS/commercial” or “open core” licensing that are forced to constantly adapt the features of the OSS and commercial parts; as we wrote:

“The model has the intrinsic downside that the FLOSS product must be valuable to be attractive for the users, but must also be not complete enough to prevent competition with the commercial one. This balance is difficult to achieve and maintain over time; also, if the software is of large interest, developers may try to complete the missing functionality in a purely open source way, thus reducing the attractiveness of the commercial version. ”

In other words, if the OSS product is too good, few will be interested in getting the commercial part, while if the OSS product is useless, the number of “adopters” will be too low to increase visibility of the product. This balance changes with time, and for this reason companies adopting this model need to constantly update their offering, and evaluate with time how to split the development effort across paid and OSS branches.

As I wrote in the beginning, there are many different adoption processes in open source software; some of those mechanisms are:

- diffusion/dissemination

- cluster propagation

- directed incentives

- enforcement

In the following posts I will try to provide some insight into each, and how to help an OSS company in leveraging the relevant process to help in both adoption and monetization.