“How do you make money with Free Software?” was a very common question just a few years ago. Today, that question has evolved into “What are successful business strategies that can be implemented on top of Free Software?”

This is the beginning of a document that I originally prepared as an appendix for an industry group white paper; as I received many requests for a short, data-concrete document to be used in university courses on the economics of FLOSS, I think that this may be useful as an initial discussion paper. A pdf version is available here for download. Data and text was partially adapted from the results of the EU projects FLOSSMETRICS and OpenTTT (open source business models and adoption of OSS within companies), COSPA (adoption of OSS by public administrations in Europe), CALIBRE and INES (open source in industrial environments). I am indebted with Georg Greve of FSFE, that wrote the excellent introduction (more details on the submission here), and that kindly permitted redistribution. This text is licensed under CC-by-SA (attribution, sharealike 3.0) . I would grateful for an email to indicate use of the text, as a way to keep track of it, at cdaffara@conecta.it.

Free Software (defined 1985) is defined by the freedoms to use, study, share, improve. Synonyms for Free Software include Libre Software (c.a. 1991), Open Source (1998), FOSS and FLOSS (both 200X). For purposes of this document, this usage is synonymous with “Open Source” by the Open Source Initiative (OSI).

Economic Free Software Perspectives

Introduction

“How do you make money with Free Software?” was a very common question just a few years ago. Today, that question has evolved into “What are successful business strategies that can be implemented on top of Free Software?” In order to develop business strategies, it is first necessary to have a clear understanding of the different aspects that you seek to address. Unfortunately this is not made easier by popular ambiguous use of some terms for fundamentally different concepts and issues, e.g. “Open Source” being used for a software model, development model, or business model.

These models are orthogonal, like the three axes of the three-dimensional coordinate system, their respective differentiators are control (software model), collaboration (development model), revenue (business model).

The software model axis is the one that is discussed most often. On the one hand there is proprietary software, for which the vendor retains full control over the software and the user receives limited usage permission through a license, which is granted according to certain conditions. On the other hand there is Free Software, which provides the user with unprecedented control over their software through an ex-ante grant of irrevocable and universal rights to use, study, modify and distribute the software.

The development model axis describes the barrier to collaboration, ranging from projects that are developed by a single person or vendor to projects that allow extensive global collaboration. This is independent from the software model. There is proprietary software that allows for far-reaching collaboration, e.g. SAP with it’s partnership program, and Free Software projects that are developed by a single person or company with little or no outside input.

The business model axis describes what kind of revenue model was chosen for the software. Options on this axis include training, services, integration, custom development, subscription models, “Commercial Off The Shelve” (COTS), “Software as a Service” (SaaS) and more.

These three axes open the space in which any software project and any product of any company can freely position itself. That is not to say all these combinations will be successful. A revenue model based on lock-in strategies with rapid paid upgrade cycles is unlikely to work with Free Software as the underlying software model. This approach typically occurs on top of a proprietary software model for which the business model mandates a completed financial transaction as one of the conditions to grant a license.

It should be noted that the overlap of possible business models on top of the different software models is much larger than usually understood. The ex-ante grant of the Free Software model makes it generally impossible to attach conditions to the granting of a license, including the condition of financial transaction. But it is possible to implement very similar revenue streams in the business model through contractual constructions, trademarks and/or certification.

Each of these axes warrants individual consideration and careful planning for the goals of the project. If, for instance the goal is to work with competitors on a non-differentiating component in order to achieve independence from a potential monopolistic supplier, it would seem appropriate to focus on collaboration and choose a software model that includes a strong Copyleft licence. The business model could potentially be neglected in this case, as the expected return on investment comes in the form of strategic independence benefits, and lower licence costs. In another case, a company might choose a very collaborative community development model on top of a strong Copyleft licence, with a revenue model based on enterprise-ready releases that are audited for maturity, stability and security by the company for its customers. The number of possible combinations is almost endless, and the choices made will determine the individual character and competitive strengths and weaknesses of each company. Thinking clearly about these parameters is key to a successful business strategy.

Strategic use of Free Software vs. Free Software Companies

According to Gartner, usage of Free Software will reach 100 percent by November 2009. That makes usage of Free Software a poor criterion for what makes a Free Software company. Contribution to Free Software projects seems a slightly better choice, but as many Free Software projects have adopted a collaborative development model in which the users themselves drive development, that label would then also apply to companies that aren’t Information Technology (IT) companies.

IT companies are among the most intensive users of software, and will often find themselves as part of a larger stack or environment of applications. Being part of that stack, their use of software not only refers to desktops and servers used by the company’s employees, but also to the platform on top of which the company’s software or solution is provided.

Maintaining proprietary custom platforms for a solution is inefficient and expensive, and depending upon other proprietary companies for the platform is dangerous. In response, large proprietary enterprises have begun to phase out their proprietary platforms and are moving towards Free Software in order to leverage the strategic advantages provided by this software model for their own use of software on the platform level. These companies will often interact well with the projects they depend upon, contribute to them, and foster their growth as a way to develop strategic independence as a user of software.

What makes these enterprises proprietary is that for the parts where they are not primarily users of software, but suppliers to their downstream customers, the software model is proprietary, withholding from its customers the same strategic benefits of Free Software that the company is using to improve its own competitiveness.

From a customer perspective, that solution itself becomes part of the platform on which the company’s differentiating activities are based. This, as stated before, is inefficient, expensive and a dangerous strategy.

Assuming a market perspective, it represents an inefficiency that provides business opportunity for other companies to provide customers with a stack that is Free Software entirely, and it is strategically and economically sane for customers to prefer those providers over proprietary ones for the very same reasons that their proprietary suppliers have chosen Free Software platforms themselves.

Strategically speaking, any company that includes proprietary software model components in its revenue model should be aware that its revenue flow largely depends upon lack of Free Software alternatives, and that growth of the market, as well as supernatural profits generated through the proprietary model both serve to attract other companies that will make proprietary models unsustainable. When that moment comes, the company can either move its revenue model to a different market, or it has to transform its revenue source to work on top of a software model that is entirely Free Software.

So usage of and contribution to Free Software are not differentiators for what makes a Free Software company. The critical differentiator is provision of Free Software downstream to customers. In other words: Free Software companies are companies that have adopted business models in which the revenue streams are not tied to proprietary software model licensing conditions.

Economic incentives of Free Software adoption

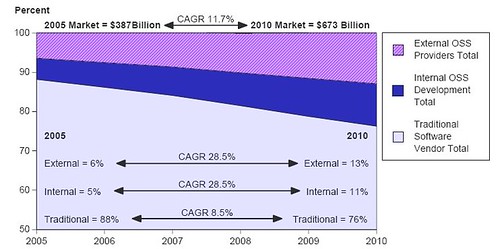

The broad participation of companies and public authorities in the Free Software market is strictly related to an economic advantage; in most areas, the use of Free Software brings a substantial economic advantage, thanks to the shared development and maintenance costs, already described by researchers like Gosh, that estimated an average R&D cost reduction of 36%. The large share of “internal” Free Software deployments explains why some of the economic benefits are not perceived directly in the business service market, as shown by Gartner:

Gartner predicts that within 2010 25% of the overall software market will be Free Software-based, with rougly 12% of it “internal” to companies and administrations that adopt Free Software. The remaining market, still substantial, is based on several different business models, that monetize the software using different strategies.

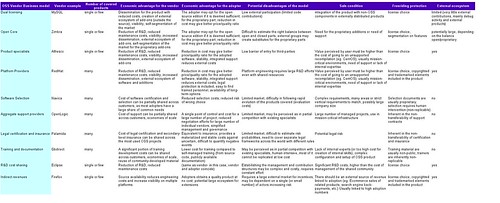

A recent update (february 2009) of the FLOSSMETRICS study on Free Software-based business model is presented here, after an analysis of more than 200 companies; the main models identified in the market are:

- Dual licensing: the same software code distributed under the GPL and a proprietary license. This model is mainly used by producers of developer-oriented tools and software, and works thanks to the strong coupling clause of the GPL, that requires derivative works or software directly linked to be covered under the same license. Companies not willing to release their own software under the GPL can obtain a proprietary license that provides an exemption from the distribution conditions of the GPL, which seems desirable to some parties. The downside of dual licensing is that external contributors must accept the same licensing regime, and this has been shown to reduce the volume of external contributions, which are limited mainly to bug fixes and small additions.

- Open Core (previously called “split Free Software/proprietary” or “proprietary value-add”): this model distinguishes between a basic Free Software and a proprietary version, based on the Free Software one but with the addition of proprietary plug-ins. Most companies following such a model adopt the Mozilla Public License, as it allows explicitly this form of intermixing, and allows for much greater participation from external contributions without the same requirements for copyright consolidation as in dual licensing. The model has the intrinsic downside that the Free Software product must be valuable to be attractive for the users, i.e. it should not be reduced to “crippleware”, yet at the same time should not cannibalise the proprietary product. This balance is difficult to achieve and maintain over time; also, if the software is of large interest, developers may try to complete the missing functionality in Free Software, thus reducing the attractiveness of the proprietary version and potentially giving rise to a full Free Software competitor that will not be limited in the same way.

- Product specialists: companies that created, or maintain a specific software project, and use a Free Software license to distribute it. The main revenues are provided from services like training and consulting (the “ITSC” class) and follow the original “best code here” and “best knowledge here” of the original EUWG classification [DB 00]. It leverages the assumption, commonly held, that the most knowledgeable experts on a software are those that have developed it, and this way can provide services with a limited marketing effort, by leveraging the free redistribution of the code. The downside of the model is that there is a limited barrier of entry for potential competitors, as the only investment that is needed is in the acquisition of specific skills and expertise on the software itself.

- Platform providers: companies that provide selection, support, integration and services on a set of projects, collectively forming a tested and verified platform. In this sense, even GNU/Linux distributions were classified as platforms; the interesting observation is that those distributions are licensed for a significant part under Free Software licenses to maximize external contributions, and leverage copyright protection to prevent outright copying but not “cloning” (the removal of copyrighted material like logos and trademark to create a new product)1. The main value proposition comes in the form of guaranteed quality, stability and reliability, and the certainty of support for business critical applications.

- Selection/consulting companies: companies in this class are not strictly developers, but provide consulting and selection/evaluation services on a wide range of project, in a way that is close to the analyst role. These companies tend to have very limited impact on the Free Software communities, as the evaluation results and the evaluation process are usually a proprietary asset.

- Aggregate support providers: companies that provide a one-stop support on several separate Free Software products, usually by directly employing developers or forwarding support requests to second-stage product specialists.

- Legal certification and consulting: these companies do not provide any specific code activity, but provide support in checking license compliance, sometimes also providing coverage and insurance for legal attacks; some companies employ tools for verify that code is not improperly reused across company boundaries or in an improper way.

- Training and documentation: companies that offer courses, on-line and physical training, additional documentation or manuals. This is usually offered as part of a support contract, but recently several large scale training center networks started offering Free Software-specific courses.

- R&D cost sharing: A company or organization may need a new or improved version of a software package, and fund some consultant or software manufacturer to do the work. Later on, the resulting software is redistributed as open source to take advantage of the large pool of skilled developers who can debug and improve it. A good example is the Maemo platform, used by Nokia in its Mobile Internet Devices (like the N810); within Maemo, only 7.5% of the code is proprietary, with a reduction in costs estimated in 228M$ (and a reduction in time-to-market of one year). Another example is the Eclipse ecosystem, an integrated development environment (IDE) originally released as Free Software by IBM and later managed by the Eclipse Foundation. Many companies adopted Eclipse as a basis for their own product, and this way reduced the overall cost of creating a software product that provides in some way developer-oriented functionalities. There is a large number of companies, universities and individual that participate in the Eclipse ecosystem; as an example:

As recently measured, IBM contributes for around 46% of the project, with individuals accounting for 25%, and a large number of companies like Oracle, Borland, Actuate and many others with percentages that go from 1 to 7%. This is similar to the results obtained from analysis of the Linux kernel, and show that when there is an healthy and large ecosystem the shared work reduces engineering cost significantly; it is estimated that it is possible to obtain savings in terms of software research and development of 36% through the use of Free Software; this is, in itself, the largest actual “market” for Free Software, as demonstrated by the fact that the majority of developers are using at least some Free Software within their own code (56.2%).

As recently measured, IBM contributes for around 46% of the project, with individuals accounting for 25%, and a large number of companies like Oracle, Borland, Actuate and many others with percentages that go from 1 to 7%. This is similar to the results obtained from analysis of the Linux kernel, and show that when there is an healthy and large ecosystem the shared work reduces engineering cost significantly; it is estimated that it is possible to obtain savings in terms of software research and development of 36% through the use of Free Software; this is, in itself, the largest actual “market” for Free Software, as demonstrated by the fact that the majority of developers are using at least some Free Software within their own code (56.2%). - Indirect revenues: A company may decide to fund Free Software projects if those projects can create a significant revenue source for related products, not directly connected with source code or software. One of the most common cases is the writing of software needed to run hardware, for instance, operating system drivers for specific hardware. In fact, many hardware manufacturers are already distributing gratis software drivers. Some of them are already distributing some of their drivers (specially those for the Linux kernel) as Free Software.

The loss-leader is a traditional commercial model, common also outside of the world of software; in this model, effort is invested in a Free Software project to create or extend another market under different conditions. For example, hardware vendors invest in the development of software drivers for Free Software operating systems (like GNU/Linux) to extend the market of the hardware itself. Other ancillary models are for example those of the Mozilla foundation, which obtains a non trivial amount of money from a search engine partnership with Google (an estimated 72M$ in 2006), while SourceForge/OSTG receives the majority of revenues from ecommerce sales of the affiliate ThinkGeek site

We found (confirming previous research from the 451 group) that at the moment there is no “significant” model, with companies more or less adopting and changing model depending on the specific market or the shifting costs. For example, during 2008 a large number of companies shifted from an “open core” model to a pure “product specialist” one to leverage the external community of contributors.

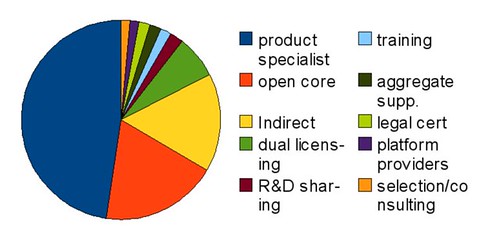

According to the collected data, among Free Software companies the “Fully Free Software” approach is still prevalent, followed by the “Open Core” and the “Dual Licensing” mode:

| Model name | # companies |

| product specialist | 131 |

| open core | 52 |

| Indirect | 44 |

| dual licensing | 19 |

| R&D sharing | 6 |

| training | 5 |

| aggregate supp. | 5 |

| legal cert | 5 |

| platform providers | 4 |

| selection/consulting | 4 |

Some companies have more than one principal model, and thus are counted twice; in particular, most dual licensing companies are also selling support services, and thus are marked as both. Also, product specialists are counted only when there is a demonstrable participation of the company into the project as “main committer”; otherwise, the number of specialists would be much greater, as some projects are the center of commercial support from many companies (a good example is OpenBravo or Zope).

Another relevant consideration is the fact that platform providers, while limited in number, tend to have a much larger revenue rate than both specialists or open core companies.

Many researchers are trying to identify whether there is a more “efficient” model among all those surveyed; what we found is that the most probable future outcome will be a continuous shift across model, with a long-term consolidation of development consortia (like Symbian and Eclipse) that provide strong legal infrastructure and development advantages, and product specialists that provide vertical offerings for specific markets. This contrasts with the view that, for example, “mixed” models provide an inherent advantage; for example, Matthew Aslett of the 451 group (one of the leading researchers in Free Software business models) wrote:

“The Open-Core approach is mostly (though not exclusively) used by vendors that dominate their own development communities. While this provides benefits in terms of controlling the direction of development and benefiting from the open source distribution model there are also risks involved with promoting and managing community development – or not. In fact, many of these companies employ the majority of the developers on the project, so they are actually missing out on many of the benefits of the open source development model (more eyeballs, lower costs etc).

Additionally, by providing revenue-generating features on top of open source code, Open-Core vendors are attempting to both disrupt their segment and profit from that disruption. I previously argued that “it is probably easier in the long-term to generate profit from adjacent proprietary products than it is to generate profit from proprietary features deployed on top of the commoditized product.”

While Open-Core is definitely the commercial open source strategy of the day and is effective in building the revenue growth required to fuel an exit strategy, I have my doubts as to whether it is sustainable in the long-term due to a combination of the issues noted above.”

The fact that Free Software is in a sense a non-rival good also facilitates cooperation between companies, both to increase the geographic base and to be able to engage large scale contracts that may require multiple competencies. Three main collaboration strategies were identified among smaller companies: geographical (same product or service, different geographical areas); “vertical” (among products) or “horizontal” (among activities). Geographic cooperation is simpler, and tends to be mainly service-based; an example is the Zope Europe Association, that unites many service providers centered on specific Zope and Plone expertise. Vertical cooperation is done by companies that performs an integrated set of activities on one or more packages. Multiple vendors with overlapping products can collaborate on a single offer (eg. operating system and Groupware), that may form a more interesting or complete offer for the selected customer segment.

The summary table is available here along with a rationale for the categories used; linked below to a public Google docs document:

Bibliography:

[451 08]The 451 group, Open source is not a business model.

[Car 07]Carbone, P. Value Derived from Open Source is a Function of Maturity Levels, OCRI conference “Alchemy of open source businesses”, 2007

[DB 00]Daffara, C. Barahona, J.B. Free Software/Open Source: Information Society Opportunities for Europe? working paper

[Daf 06]Daffara, C. Sustainability of FLOSS-based business models, II Open Source World Conference, Malaga 2006

[Daf 06-2]Daffara, C. Introducing open source in industrial environments. 3rd CALIBRE workshop

[Daf 07]Daffara, C. Business models in OSS-based companies. OSSEMP workshop, Third international conference on open source. Limerick 2007

[ED 05]Evans Data, Open Source Vision report, 2005

[Gar 06]Gartner Group, Open source going mainstream. Gartner report, 2006

[Gosh 06]Gosh, et al. Economic impact of FLOSS on innovation and competitiveness of the EU ICT sector.

[IDC 06]IDC, Open Source in Global Software: Market Impact, Disruption, and Business Models. IDC report, 2006

[Jul 06]Jullien N. (ed) New economic models, new software industry economy. RNTL report

[VH 03]Von Hippel, E. and G. von Krogh, Open Source Software and the “Private-Collective” Innovation Model: Issues for Organizational Science. Organization Science, 2003. 14(2): p. 209-223

[VH 05]Von Hippel, E. Democratizing innovation. MIT press, 2005

#1 by Matthew Aslett - May 5th, 2009 at 14:25

Great overview Carlo.Thanks for the mention. One thing I am not clear on – and I think I asked about this before, so sorry if I am repeating myself – is: “during 2008 a large number of companies shifted from an “open core” model to a pure “product specialist” one to leverage the external community of contributors”. Any examples?

#2 by cdaffara - May 6th, 2009 at 07:25

DimDim “synchronized” the source code of the hosted version and the open source version, effectively removing the non-free parts (and some very arbitrary limits…) From the website: “We have synchronized this release to match the latest hosted version and released the complete source code tree”. There is a functionality that is not available (recording) because it is based on a commercial component that is licensed from Adobe only for the hosted edition, but as that is not due to a company licensing decision, I still count it as not open core.

OpenClinica rereleased all the code under an OS license, and left out only non-core features for the enterprise edition (mainly data acquisition forms for specific clinical practice)

TenderSystem added most of the features of the “enterprise” edition to the OSS one, with minor exception (invoicing through an external system, that it seems will be added in the future) ; the main difference is support and customization in the enterprise edition (and the availability of an hosted one).

MedSphere rereleased the entire VISTA system (that was already public domain, but with many limits), adding the needed support for GT.M in production, some of the originally excluded modules and the desktop user interface that was previously proprietary (anyway, you are not going to use it without help and certification, so it is not a loss for them…)

Here in the airport I have not my entire list with me, those are just top of my mind…