Archive for category OSS business models

The procurement advantage, or a simple test for “purity”

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on April 20th, 2009

There is no end in sight for the “open core” debate, or for the matter what role companies should have in the OSS marketplace. We recently witnessed the lively debated sparked by a post by James Dixon, that quickly prompted Tarus Balog to descent into another of his informed and passionate posts on open core and OSS. This is not the first (and will not be the last) of public discussions on what an OSS vendor is, and I briefly entered the fray as well. I am quite sure that this discussion will actually continue for a long time, just lowering its loudness and turning into the background as OSS becomes more and more entrenched inside of our economy.

There is, however, a point that I would like to make about the distinction between “pure OSS” and “open core” licensing, a point that does not imply any kind of “ethical” or “purity” measure, but just a consideration on economics. When we consider what OSS is and what advantage it brings to the market, it is important to consider that a commercial OSS transaction usually has two “concrete” partners: the seller (the OSS vendor) and the buyer, that is the user. If we look at the OSS world we can see that in both the pure and the open core model the vendor has the added R&D sharing cost reduction (that, as I wrote about in the past, can provide significant advantages). But R&D is not the only advantage: the reality is that “pure” OSS has a great added advantage for the adopter, that is the greatly reduced cost and effort of procurement.

With OSS the adopter can scale a single installation company-wide without a single call to the legal or procurement departments, and it can ask support from the OSS vendor if needed- eventually after the roll-out has been performed. With open core, the adopter is not allowed to do the same thing, as the proprietary extensions are not under the same license of the open source part; so, if you want to extend your software to more servers, you are forced to ask the vendor- exactly the same of proprietary software systems. This is, in fact, a much overlooked advantage of OSS, that is especially suited to those “departmental” installations that would be probably prohibited if legal or acquisition department would have to be asked for budget.

I believe that this advantage is significant and largely hidden. I started thinking about it while helping a local public administration in the adoption of an OSS-based electronic data capture for clinical data, and discovered that for many authorities and companies procurement (selecting the product, tendering, tender evaluation, contracting, etc.) can introduce many months in delays, and substantially increase costs. For this reason, we recently introduced with our customers a sort of “quick test” for OSS purity:

The acquired component is “pure OSS” if (eventually after an initial payment) the customer is allowed to perform extensions to its adoption of the component inside and outside of its legal border without the need for further negotiation with the vendor.

The reason for that “eventually after an initial payment” because the vendor may decide to release the source code only to customers (this is something that is allowed by some licenses), and the “inside and outside of its legal border” is a phrase that explicitly includes not only redistribution and usage within a single company, but also to external parties that may be not part of the same legal entity. This distinction may not be important for small companies, but may be vital for example for public authorities that need to redistribute a software solution to a large audience of participating public bodies (a recent example I found is a regional health care authority, that is exploring an OSS solution to be distributed to hospital, medical practitioners and private and public structures). Of course, this does not imply that the vendor is forced to offer services in the same way (services and software are in this sense quite distinct) or that the adopter should prefer “pure OSS” over “open core” (in fact, this is not an expression of preference for one form over the other).

We found this simple test to be useful especially for those new OSS adopters that are not overly interested in the intricacies of open source business models, and makes for a good initial question to OSS vendors to understand what are the implication of acquiring a pure vs. an open core solutions.

A brief research summary

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on April 17th, 2009

After two months and 24 posts, I would like to thank all the kind people that mentioned our FLOSSMETRICS and OpenTTT work, especially Matthew Aslett, Matt Asay, Tarus Balog, Pamela Jones and many others with which I had the pleasure to exchange views with. I received many invaluable suggestions, and one of the most common one was to have a small “summary” of the posted research, as a landing page. So, here is a synthesis of the previous research posts:

- Why use OSS in product development: a set of examples from a thesis by Erkko Anttila, “Open Source Software and Impact on Competitiveness: Case Study” from Helsinki University of Technology, that provided hard data on the different hybrid community/company approaches by Nokia and Apple, and the relative gains and advantages.

- The dynamics of OSS adoption – 1: an initial view on the different dynamics behind open source adoption, starting with diffusion processes. Some data was also presented on unconstrained monetization.

- On business models and their relevance: A follow-up post on work by Matthew Aslett, introducing my view that future OSS business models will see more industry consortia and specialists, as more and more groups start to take advantage of the collaborative model, and will need more coordination on how to contribute back.

- Transparency and dependability for external partners: Outlining the transparency advantages of most OSS projects (with two examples mentioned: Zimbra and Alfresco) and the added advantage for partners, that can synchronize their work with that of the OSS community.

- The dynamics of OSS adoptions, II – diffusion processes: A presentation of diffusion processes as one of the models in OSS adoption, and a presentation of the UTAUT model for estimating the degree of acceptance of OSS.

- From theory to practice: the personal desktop linux experiment: A (long) example on how to apply the previously discussed models in a theoretical exercise: creating an end-user, large scale linux PC for personal activities. The post was inspired by work done during the Manila workshop along with UN’s International Open Source Network for facilitating take-up of open source by south-east Asean SMEs.

- Rethinking OSS business model classifications by adding adopters’ value: A presentation of the new classification of OSS business models; I have to thank Matthew Aslett of the 451 group for the many comments, and for accepting to share his work from the CAOS report with us.

- Comparing companies effectiveness: a response to Savio Rodrigues: A post written in response to work by Savio Rodrigues, on the relative shares of R&D of OSS companies compared to traditional IT companies.

- Our definitions of OSS-based business models: A follow-up of the “rethinking..” post, it outlines the new definitions of OSS business models created for the final part of the FLOSSMETRICS project.

- Another take on the financial value of open source: Our estimates of the value of the open source software market, and a call for further research on non-code contributions.

- OSS-based business models: a revised study based on 218 companies: A post providing the summary of the extended FLOSSMETRICS study on open source companies, that increased its number from 80 to 218, with some observation on relative size and usage of the various models.

- Estimating savings from OSS code reuse, or: where does the money comes from?: One of my favourite posts, provides a long discussion of the savings obtained when using OSS inside of other products, with some additional data obtained through COCOMO modeling.

- Another data point on OSS efficiency: A short post focusing on data from the italian TEDIS research, that showed how OSS companies are on average more capable to take on larger customers when compared with benchmark IT companies of the same size.

- The new FLOSSMETRICS project liveliness parameters: Fresh from the other project researchers, I provided a list of the new “project liveness” parameters that will be used in the SME guide.

- Reliability of open source from a software engineering point of view: A post that presents some results on how open source tends to be of higher quality under specific circumstances, and a follow-up idea on how this may be due to basic software engineering facts (related to component reuse).

- Open source and certified systems: A post inspired by a recent white paper on e-voting, the post presents my views on high-integrity and life-critical open source systems.

Open source and certified systems

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on April 16th, 2009

A recent white paper, published by the Election Technology Council (an industry trade association representing providers for over 90% of the voting systems used in the United States), analyses the potential role of open source software in voting systems, concludes that “it is.. premature. Given the economic dynamics of the marketplace, state and federal governments should not adopt unfair competitive practices which show preferential treatment towards open source platforms over proprietary ones. Legislators who adopt policies that require open source products, or offer incentives to open source providers, will likely fall victim to a perception of instituting unfair market practices.” (where do I have heard this? curious, sometimes, the deja vu feeling…)

The white paper however does contain some concepts that I have found over and over, the result of mixing the “legal” perspective of OSS (the license on which the software is released) with the “technical” aspects (the collaborative development model), arriving at some false conclusions that are unfortunately shared by many others. For this reason, I would like to add my perspective on the issue of “certified” source code and OSS:

- First of all, there is no causal relation between the license aspect and the quality of the code or its certifiability. It is highly ironic that the e-voting companies are complaining of the fact that OSS may be potentially not tested enough for critical environments like voting, given the results of some testing on their own software systems: “the implementation of cryptographic protection is flawed..this key is hard-coded into the source code for the AV-TSx, which is poor security practice because, among other things, it means the same key is used in every such machine in the U.S … and can be found through Google. The result is that in any jurisdiction that uses the default keys rather than creating new ones, the digital signatures provide no protection at all.” “No use of high assurance development methods: The AccuBasic interpreter does not appear to have been written using high-assurance development methodologies. It seems to have been written according to ordinary commercial practices. … Clearly there are serious security flaws in current state of the AV-OS and AV-TSx software” (source: Security Analysis of the Diebold AccuBasic Interpreter, Wagner, Jefferson, Bishop). Of course, there are many other reports and news pieces on the general unreliability of the certified GEMS software, just to pick the most talked about component. The fact is that assurance and certification is a non-functional aspect that is unrelated to the license the software is released with, as certifications of software quality and adherence to high-integrity standards are based on design documents, the adherence to development standards, testing procedures and much more- but not licensing.

- I have already written about our research on open source quality from the software engineering point of view, and in general it can be observed that open source development models tend to have an higher improvement in quality within a specific time frame when compared to proprietary software systems under specific circumstances (like a healthy contributor community).

- It is possible to certify open source systems under the strictest certification rules, like the SABI “secret and below” certification, medical CCHIT, encryption FIPS standard, common criteria Evaluation Assurance Level EAL4+ (and in one case, meet or exceed EAL5), civil engineering (where the product is used for the stability computations for EDF nuclear plants designs), avionics and ground-based high-integrity systems, like air traffic control and railrway systems (we explored the procedures for achieving certified status for pre-existing open source code in the CALIBRE project). Thus, it is possible to meet and exceed the regulatory rules for a wide spectrum of environments with far more stringent specifications than the current e-voting environment.

- It seems that the real problem lies in the potential for competition from OSS voting systems: “over proprietary ones. Legislators who adopt policies that require open source products, or offer incentives to open source providers, will likely fall victim to a perception of instituting unfair market practices. At worst, policy-makers may find themselves encouraging the use of products that do not exist and market conditions that cannot support competition.” The reality is that there are some open source voting software (the white paper even lists some), and the real threat is the government to start funding those projects instead of buying proprietary combinations. This is where the vendors clearly show the underlying misunderstanding on how open source works: you can still sell your assembly of hardware and software (as with EAL, it is the combination of both that is certified, not the software in isolation) and continue the current business model. It is doubtful that the “open source community” (as mentioned in the paper) will ever certify the code, as it is a costly and substantial effort, exactly like no individual applied to EAL4+ certification for Linux (that requires a substantial amount of money).

The various vendors would probably do something better if they started a collaborative effort for a minimum-denominator system to be used as a basis for their system, in a way similar to that performed by mobile phone companies in the LiMo and Android projects, or through industry consortia like Eclipse. They could still be introducing differentiating aspects in the hardware and upper-layer software, while reducing the costs of R&D and improving the transparency of a critical component of our modern democracies.

MXM, patents and licenses: clarity is all it takes

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on April 10th, 2009

Recently on the OSI mailing list Carlo Piana wrote a proposed license for the reference implementation of the ISO/IEC 23006 MPEG eXtensible Middleware (MXM). The license is derived from the MPL with the removal of some of the patent conditions from the text of the original license, and clearly creates a legal boundary conditions that grants patent rights only for those who compile it only for internal purposes without direct commercial exploitation. I tend to agree on Carlo’s comment: “My final conclusion is that if the BSD family is considered compliant, so shall be the MXM, as it does not condition the copyright grant to the obtaining of the patents, just as the BSD licenses don’t deal with them. And insofar an implementer is confident that the part of the code it uses if free from the patented area, or it decided to later challenge the patent in case an infringement litigation is threatened, the license works just fine.” (as a side note: I am completely and totally against software patents, and I am confident that Carlo Piana is absolutely against them as well).

Having worked in the italian ISO JTC1 chapter, I also totally agree with one point: “the sad truth is that if we did not offer a patent-agnostic license we would have made all efforts to have an open source reference implementation moot.” Unfortunately, ISO still believes that patents are something that is necessary to convince companies to participate in standard groups, despite the existence of standard groups that do work very well without this policy (my belief is that the added value of standardization in terms of cost reductions are well worth the cost of participating in the creation of complex standards like MPEG, but this is for another post).

What I would like to make clear is that the real point is not if the proposed MXM license is OSI-compliant or not: the important point is why you want it to be open source. Let’s consider the various alternatives:

- the group believes that an open source implementation may receive external effort, much like the traditional open source projects, and thus reduce maintenance and extension effort. If this is the aim, then the probability of having this kind of external support is quite low, as companies would avoid it (as the license would not allow in any case a commercial use with an associated patent license), and researchers working in the area would have been perfectly satisfied with any kind of academic or research-only license.

- the group wants to increase the adoption of the standard, and the reference implementation should be used as a basis for further work to turn it into a commercial product. This falls in the same cathegory as before; why should I look at the reference implementation, if it does not grant me any potential use? The group could have simply published the source code for the reference, and said “if you want to use it, you should pay us a license for the embedded patents”.

- the group wants to have a “golden standard” to benchmark external implementations (for example, to see that the bitstreams are compliant). Again, there is no need for having an open source license.

The reality is that there is no clear motivation behind making this under an open source license, because the clear presence of patents on the implementation makes it risky or non-free to use for any commercial exploitation. Microsoft, for example, did it much better: to avoid losing their rights to enforce their patents, they paid or supported other companies to create a patent-covered software and released it under an open source license. Since the “secondary” companies do not hold any patent, with the releasing of the code they are not relieving any threat from the original Microsoft IPR, and at the same time they use a perfectly acceptable OSI-approved license.

As the purpose of the group is twofold (increase adoption of the standards, make commercial user pay for the IPR licensing) I would propose a different alternative: since the real purpose is to get paid for the patents, or to be able to enforce them in case of commercial competitors, why don’t you dual-license it with the strongest copyleft license available (at the moment, the AGPL)? This way, any competitor would be forced to be fully AGPL (and so any improvement would have to be shared, exchanging the lost licensing revenue for the maintenance cost reduction) or to pay for the license (turning everything into the traditional IPR licensing scheme).

I know, I know – this is wishful thinking. Carlo, I understand your difficult role…

Another hypocrite post: “Open Source After ‘Jacobsen v. Katzer’”

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, divertissements on April 8th, 2009

The reality is that I am unable to resist. To see a post containing idiotic comments on open source, masqueraded as a serious article, makes me start giggling with “I have to write them something” (my coworkers are used to it – they sometimes comment with “another post is arriving” or something more humorous). The post of today is a nicely written essay from Jonathan Moskin, Howard Wettan and Adam Turkelon Law.com, with the title “Open Source After ‘Jacobsen v. Katzer’”, referring to a recent US Federal Circuit decision. The main point of the ruling is “…the Federal Circuit’s recognition that the terms in an open source license can create enforceable conditions to use of copyrighted materials”; that is, the fact that software licenses (in this case, the Artistic License) that limit redistribution are enforceable. Not only this, but the fact that the enforceability is also transferable: “because Jacobsen confirmed that a licensee can be liable for copyright infringement for violating the conditions of an open source license, the original copyright owner may now have standing to sue all downstream licensees for copyright infringement, even absent direct contractual privity”.

This is the starting point for a funny tirade like: “Before Jacobsen v. Katzer, commercial software developers often avoided incorporating open source components in their offerings for fear of being stripped of ownership rights. Following Jacobsen, commercial software developers should be even more cautious“(the article headline in the Law.com front page) to “It is perhaps also the most feared for its requirement that any source code compiled with any GPL-licensed source code be publicly disclosed upon distribution — often referred to as infection.” (emphasis mine).

Infection??

And the closing points: “Before Jacobsen v. Katzer, commercial software developers already often avoided incorporating open source components in their offerings for fear of being stripped of ownership rights. While software development benefits from peer review and transparency of process facilitated by open source, the resulting licenses, by their terms, could require those using any open source code to disclose all associated source code and distribute incorporated works royalty-free. Following Jacobsen v. Katzer, commercial software developers should be even more cautious of incorporating any open source code in their offerings. Potentially far greater monetary remedies (not to mention continued availability of equitable relief) make this vehicle one train to board with caution.”

Let’s skip the fact that the law practitioners that wrote this jewel of law journalism are part of the firm White & Case that represented Microsoft in the EU Commission’s first antitrust action; let’s skip the fact that terms like “infection” and the liberal use of “commercial” hides the same error already presented in other pearls of legal wisdom already debated here, the reality is that the entire frame of reference is based on an assumption that I heard the first time from a lawyer working for a quite large firm: that since open source software is “free”, companies are entitled to do whatever they want with it.

Of course it’s a simplification – I know many lawyers and paralegals that are incredibly smart (Carlo Piana comes to mind), but to this people I propose the following gedankenexperiment: imagine that within the text of the linked article every mention to “open source” was magically replaced with “proprietary source code”. The federal circuit ruling would more or less stay unmodified, but the comment of the writers would assume quite hysterical properties. Because they would argue that proprietary software is extremely dangerous, because if Microsoft (just as an example) found parts of its source code included inside of another product, they would sue the hell out of the poor developer, that would be unable to use the “Cisco defence”: to claim that Open Source “crept into” its products and thus damages should be minimal. The reality is that the entire article is written with a focus that is non-differentiating: in this sense, there is no difference between OSS and proprietary code. Exactly like for proprietary software, taking open source code without respecting the license is not allowed (the RIAA would say that it is “stealing”, and that the company is a “pirate”).

So, dear customers of White & Case, stay away from open source at all costs – while we will continue to reap its benefits.

See you in Brussels: the European OpenClinica meeting

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on April 8th, 2009

In a few days, the 14th of April, I will be attending as a panelist the first European OpenClinica meeting, in the “regulatory considerations” panel. It will be a wonderful opportunity to meet all the other OpenClinica users and developers, and in general talk and share experiences. As I will stay there for the evening, I would love to invite all friends and open source enthusiasts that happen to be in Brussels that night for a chat and a Belgian beer.

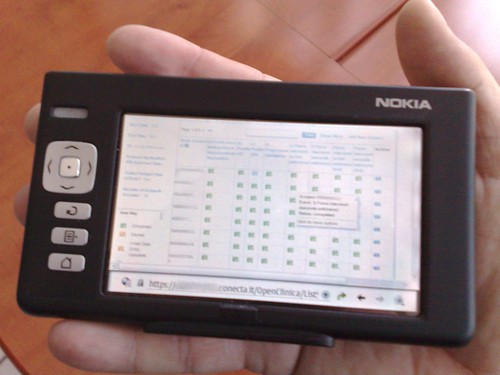

As for those that are not aware of OpenClinica: it is a shining example of open source software for health care; it is a Java-based server system that allows to create secure web forms for clinical data acquisition (and much more). The OpenClinica software platform supports clinical data submission, validation, and annotation; data filtering and extraction, study auditing, de-identification of Protected Health Information (PHI) and much more. It is distributed under the LGPL, and does have some really nice features (like the design of forms using spreadsheets – extremely intuitive).

We have used it in several regional and national trials, and even trialed it as a mobile data acquisition platform.

If you can’t be in Brussels, but are interested in open source health care, check out OpenClinica.

Reliability of open source from a software engineering point of view

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on April 6th, 2009

At the Philly ETE conference Michael Tiemann presented some interesting facts about open source quality, and in particular mentioned that open source software has an average defect density that is 50-150 times lower than proprietary software. As it stands, this statement is somewhat incorrect, and I would like to provide a small clarification of the context and the real values:

- First of all, the average that is mentioned by Michael is related to a small number of projects, in particular the Linux kernel, the Apache web server (and later the entire LAMP stack), and a small number of additional, “famous” projects. For all of these projects, the reality is that the defect density is substantially lower than that of comparable proprietary products. A very good article on this is Succi, Paulson, Eberlein. An Empirical Study of Open-Source and Closed-Source Software Products, IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SOFTWARE ENGINEERING, V.30/4, april 2004, where the study was performed. It was not the only study on the subject, but all pointed at more or less the same results.

- Other than the software engineering community, some results from companies working in the code defect identification industry also published some results, like Reasoning Inc. A Quantitative Analysis of TCP/IP Implementations in Commercial Software and in the Linux Kernel, and How Open Source and Commercial Software Compare: Database Implementations in Commercial Software and in MySQL. All results confirm the much higher quality (in terms of defect per line of code) of the academic research.

- Additional research identified a common pattern: the initial quality of the source code is roughly the same for proprietary and open source, but the defect density decreases in a much faster way with open source. So, it’s not the fact that OSS coders are on average code wonders, but that the process itself creates more opportunity for defect resolution on average. As Succi et al. pointed out: “In terms of defects, our analysis finds that the changing rate or the functions modified as a percentage of the total functions is higher in open-source projects than in closed- source projects. This supports the hypothesis that defects may be found and fixed more quickly in open-source projects than in closed-source projects and may be an added benefit for using the open-source development model.” (emphasis mine).

I have a personal opinion on why this happens, and is really related to two different phenomenons:the first aspect is related to code reuse: the general modularity and great reuse of components is in fact helping developers, because instead of recoding something (introducing new bugs) the reuse of an already debugged component reduces the overall defect density. This aspect was found in other research groups focusing on reuse; for example in a work by Mohagheghi, Conradi, Killi and Schwarz called “An Empirical Study of Software Reuse vs. Defect-Density and Stability” (available here) we can find that reuse introduces a similar degree of improvement in the bug density and the trouble report numbers of code:

As it can be observed from the graph, code originated from reuse has a significant higher quality compared to traditional code, and the gap between the two grows with the size (as expected from basic probabilistic models of defect generation and discovery).

The second aspect is that the fact that bug data is public allows a “prioritization” and a better coordination of developers on triaging and in general fixing things. This explains why this faster improvement appears not only in code that is reused, but in newly generated code as well; the sum of the two effects explains the incredible difference in quality (50-150 times), higher than any previous effort like formal methods, automated code generation and so on. And this quality differential can only grow with time, leading to a long-term push for proprietary vendor to include more and more open source code inside of their own products to reduce the growing effort of bug isolation and fixing.

Dissecting words for fun and profit, or how to be a few years too late

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, divertissements on April 3rd, 2009

So, after finishing a substantial part of our work on FLOSSMETRICS yesterday, I believe that I deserve some fun. And I cannot ask more than a new, flame-inducing post from a patent attorney, right here, that claims that open source will destroy the software industry, just waiting to be dissected and evaluated- he may be right, right? Actually, not; but as I have to rest somehow between my research duties with the Commission, I decided to prepare a response- after all, the writer is a fellow EE (electrical engineer), and so he will probably enjoy some response to his blog post.

Let’s start by stating that the idea that OSS will destroy the software industry is not new; after all, it is one of the top 5 myths from Navica, and while no-one tried to say that in front of me, I am sure that it was quite common, a few years ago. Along with the idea that software helps terrorists:

‘Now that foreign intelligence services and terrorists know that we plan to trust Linux to run some of our most advanced defense systems, we must expect them to deploy spies to infiltrate Linux. The risk is particularly acute since many Linux contributors are based in countries from which the U.S. would never purchase commercial defense software. Some Linux providers even outsource their development to China and Russia.’ (from Green Hills Software CEO, Dan O’Dowd).

So, let’s read and think about what Gene Quinn writes:

“It is difficult, if not completely impossible, to argue the fact that open source software solutions can reduce costs when compared with proprietary software solutions, so I can completely understand why companies and governments who are cash starved would at least consider making a switch, and who can fault them for actually making the switch.”

Nice beginning, quite common in debate strategy: first, concede something to the opponent. Then, use the opening to push something unrelated:

“The question I have is whether this is in the long term best interest of the computing/software industry. What is happening is that open source solutions are forcing down pricing and the race to zero is on.”

Here we take something that is acknowledge (that OSS solutions are reducing costs, thus creating a pressure on pricing) and then we attach a second, logically unconnected term: “the race to zero is on”. Who says that the reduction in pricing leads to a reduction to zero? No one with an economics background. The reality is that competition brings down prices, theoretically (in a perfectly competitive environment made of equal products) bringing the price down to the marginal cost of production. Which is, of course, not zero- as any software company will happily tell you. Because the cost of producing copies of software is very small, but the cost of creating, supporting, maintaining, documenting software is not zero. This does not take into account the fact that some software companies enjoy profit margins unheard of, and this explains why there is such a rush by users in at least experimenting with potentially cost-saving measures.

“as zero is approached, however, less and less money will be available to be made, proprietary software giants will long since gone belly-up and leading open source companies, such as Red Hat, will not be able to compete.“

Of course, since zero is not approached, the phrase is logically useless (what is the color of my boat? any as you like- as I don’t own one). But let’s split it in parts anyway: of course, if zero is approached, software giants will go belly-up. But why RedHat will not be able to compete? Compete with what? If all proprietary companies will disappear, and only OSS companies remains, then the market actually increases, even with increasingly small revenues; the same effect that can be witnessed in some mobile data markets, with the reduction in price of SMS you see an increase in the number of messages sent, resulting in an increase in revenues.

“It is quite possible that the open source movement will ultimately result in a collapse of the industry, and that would not be a good thing.“

Still following the hypothetical theory that software pricing will go to zero (that, as I said, is not grounded in reality) here the author takes the previous considerations and uses a logical trick; he says that the proprietary companies will disappear, here he says that there will be a collapse of the industry (not of the “proprietary industry”). This way he collapses the concept of the software industry (that includes the proprietary and the non-proprietary actors) and conveniently avoids the non-proprietary part. Of course, this is still not grounded in anything logical. The conclusion is obvious: “that would not be a good thing”. Of course, this is another rhetoric form- by adding a “grounding” in something that is emotionally or ethically based, we introduce an external negative perception in the reader, strengthening what is still an hypothesis.

And then, the avoidance trap:

“I am sure that many open source advocates who are reading this are already irate, and perhaps even yelling that this Quinn guy doesn’t know what he is talking about. I am used to it by now; I get it all the time. It is, after all, much easier to simply believe that someone you disagree with is clueless rather than question your own beliefs“

This approach is so commonly used that is now beginning to show its age; use the fact that someone may be irate at reading the article to dismiss all critics as clueless people unable to question “beliefs”. The use of this word is another standard tactics, simply removing the idea that the personal position of an OSS adopter depends on illogic, faith-based assumptions; this, of course, would be difficult to defend in an academic environment, where we assume that researchers are not faith-based in their studies. So, this is an approach commonly used in online forum, blogs and such that are meant for a general audience.

“It is a mistake though to dismiss what I am saying here, or any of my other writings on computer software and open source.“

Of course, I am dismissing it for the content of what you write, not because of my “beliefs”; and I have not read anything else from you, so I am not dismissing what I have not read.

“The fact that I am a patent attorney undoubtedly makes many in the open source movement immediately think I simply don’t understand technology, and my writings that state computer software is not math have only caused mathematicians and computer scientists to believe I am a quack.“

This is totally unrelated to the previous arguments- who was talking of software patents anyway? We were talking about the role of OSS in terms of competition with the proprietary software market, and about potential effects to revenues.

“Unlike most patent attorneys, I do get it and that is probably why my writings can be so offensive to the true believers. I am not only a patent attorney, but I am an electrical engineer who specializes in computer technologies, including software and business method technologies. I write software code and whether you agree with me or not, telling me I simply don’t understand is not intellectually compelling.“

Of course, being part of a “class of people” like EE is in itself not qualifying in any way; any comment I made up to now would be equally applicable independently of the author; claiming to “get it” or implying that someone “don’t get it” because he works as a patent attorney is silly, and here the author falls in the same fallacy. By the way, I know some patent attorneys that perfectly “get it”, along with others that believe that open source software is made by fairies in the forest. As I said, being member of a class is in itself useless in deciding the truth of a statement.

“I do get it, and the reality is that open source software is taking us in a direction that should scare everyone.“

Here the author uses the fallacy of membership discussed before, and uses it as a authority power: “I do get it”. I am qualified, then I am saying the truth. And what I am saying is that OSS is dangerous, and the fact that anyone else (apart from O’Dowd, that believes that Linux will be infiltrated by terrorists) is not perceiving the problem is due to the fact that they are not looking with enough attention.

“Sun Microsystems is struggling, to say the least, and the reality is that they are always going to struggle because they are an open source company, which means that the only thing they can sell is service.“

Sun Microsystems is struggling for a long time now (unfortunately; I always loved their products). Personally I believe that the new CEO is doing quite a turnaround on the company, that has languished for a long time on a shrinking, highly lucrative market like SGI did in the past, but that is better left to financial analysts. Anyway their financial results were not that good even before the OSS turnaround imposed by Jonathan Schwartz, and so there is no real linking between the two part of the phrase (on the contrary, the OSS part is growing nicely, while the large scale enterprise server part is decreasing fast). It also introduces an additional error, that is the fact that being OSS means that you can sell only services. The author clearly has not read much on OSS business models, but he should not worry: I would be happy to send some papers on the subject.

“Whenever you sell time, earning potential is limited. There are only so many hours in the day, and only so much you can charge by the hour. When you have a product that can be replicated, whether it be a device, a piece of proprietary software or whatever, you have the ability to leverage, which simply doesn’t exist when you are selling yourself by the hour.“

Of course: this is the reality of consulting. This, however, does not stop companies like IBM Global Services, Accenture and friends to live off consulting, simply by asking very high prices for a day of a specialized consultant. Or, you can find groups like the 451 or RedMonk that are more efficient and targeted towards special markets.

“So there is a realistic ceiling on the revenue that can be earned by any open source company, and that ceiling is much lower than any proprietary software company.“

So, assuming that by-the-hour services is the only OSS business model possible, and that the price-per-hour cannot match that of large consulting firm, then there is a revenue ceiling that is lower than that of proprietary software companies. The fact that both parts of the phrase are unsustained by arguments makes the conclusion unproven.

“It is also an undeniable truth that the way many, if not most, service companies compete is by price. When service companies try and get you to switch over they will promise to provide the same or better service for a lower price.”

This should be a supporting argument for the fact that OSS companies charge a lower per-hour price of competing companies, and uses Sun as an example. Of course, it continues to be an unsupported argument, even considering the fact that the author probably never paid a receipt for a Sun consultant, or would have discovered that their pricing is in line with the rest of the market.

“The trouble with freeware is that there is no margin on free, and while open source solutions are not free, the race to asymptotically approach free is on, hence why I say the race to zero is in full swing.”

Now the author switches from OSS to “freeware”, to remind us that Open Source is, after all, free. Probably RMS would say at this point “free as in free speech, not free as in free beer”, but his ideas would be probably dismissed. The use of “free” here is made to create the appearance of a logical connection between “freeware” and open source; of course, the author acqnowledges that OSS is not free, but as part of the same “family” they are participating in the “asymptotically approach free… race to zero”. As stated before: in a perfect competition the race is not to zero, but to the marginal cost; so using “freeware” is a way to imply that this cost is zero as well, when the reality is that it is not zero (but lower than writing everything from scratch, thanks to the reuse opportunity).

And then we move to something completely different (as Monty Python would say):

“Unfortunately, many in the patent legal community are engaging in the race to zero as well. For example, there are patent attorneys and patent agents who advertise online claiming to be able to draft and file a complete patent application for under $3,000. One of the most common ads running provides patent applications for $2,800, and I have seen some agents advertise prices as low as $1,400 for a relatively simple mechanical invention. The race to zero is in full swing with respect to patent services aimed at independent inventors and start-up companies. It is also being pushed by major companies who want large law firms to provide patent services for fees ranging from $3,500 to $7,000 per application. This is forcing many large patent law firms to simply not offer patent drafting and prosecution services any longer. There are major law firms that are seeking to outsource such work, hoping to still keep the client for litigation purposes and to negotiate business deals.“

Dear writer, this is called “competition”. And as before, it is not a “race to zero”, as you will never find an attorney doing this kind of service for free, without any attachment; or if they do, they will probably go out of business, leaving the market.

“Does anyone really think that paying $1,400 for an allegedly complete patent application is a wise business decision? I can’t imagine that if you say that to yourself out loud it would sound like such a good idea.“

Well, IF the author can prove that application quality and price are correlated, then this becomes a decision based on economics principles (and depends on the hypothetical future value of the patent, measures of indirect value and so on). If the correlation is not strict, then any rational actor would simply seek the lowest possible price.

“Likewise, Fortune 500 companies that are pushing prices down and wanting to pay only $3,500 for a patent application can’t really expect to get much, if any, worthwhile protection. Do they? I suppose they do, but the reality is that they don’t. The reality is that when you are drafting a patent application you can ALWAYS make it better by spending more time. … But to think that you can force a patent attorney or agent to spend the same length of time working on a project whether you pay under $3,500, $7,000 or $10,000 is naïve. Everyone inherently knows this to be true, but somehow convinces themselves otherwise“

So, Fortune 500 companies are managed by morons, that don’t understand the value of spending more time. I suspect it is for a lack of culture, or a lack of perception of value; both can be cured by promotion and dissemination of information. Still, this does not applies to Open Source.

“As companies continue to look for the low cost solution, quality is sacrificed.“

Ah! Here’s the connection! As for patent applications, software has the same correlation: quality-price…

“Now I full well realize that much of the open source software is better than proprietary software, and I know that it can be much cheaper to rely on open source solutions than to enter into a license agreement for proprietary software.“

…but I can’t say it loud, thinks the author, or they will burn me alive. So, let’s change the subject again:

“But where is that going to lead us? Once mighty Sun Microsystems is hanging on for dear life, and is that who you want to be relying on to provide service for your customized open source solutions? What if Sun simply disappears?“

Can you trust a company like Sun, that by using OSS is destroying itself? Or are you thinking about using OSS, and take the risk of being such a dying corpse yourself? So, let’s make sure that the poor moron that thinks that OSS can save money understand the risks, by bringing another example: gyms!

“I remember years ago I joined a gym and purchased a yearly membership only to have the gym close less than 2 months later. A similar thing happened to my wife several years ago when she bought a membership to a fitness and well-being company who shall remain nameless. Eat better and get exercise counseling and support, what a deal! Of course, it was a deal only until the company filed for bankruptcy and left all its members high and dry. Luckily I put off joining myself otherwise we would have been out two memberships after less than 30 days.“

Of course, the parallel between gyms and software companies is not so strict; and is not related to OSS at all – examples abound of what happens, in all sectors. At least, with OSS, you have the source code, and you can do something yourself.

“With once mighty companies falling left and right do you really want to bet the IT future of your company or organization on an industry whose business model is the race to zero?”

So, dear author, the race is not to zero, and yes, I would bet it on open source, so at least I am free to continue to use your gym even after it has closed.

The new FLOSSMETRICS project liveliness parameters

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on April 2nd, 2009

While working on the final edition of our FLOSSMETRICS guide on OSS, I received the new automated estimation procedures from the other participants in the project and the QUALOSS people, namely Daniel Izquierdo. Santiago Dueñas and Jesus Gonzales Barahona from the Departamento de Sistemas Telemáticos y Computación (GSyC) of the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. The new parameters will be included soon in the automated project page that is created in the FLOSSMETRICS database (here is an example for the Epiphany web browser); and will feature a very nice colour-coded scheme that provides an at-a-glance view of the risks or strengths of a project. A nice feature of FLOSSMETRICS is the fact that it provides information not only on code, but on ancillary metrics like mailing lists, committers participation, and so on, and all the tools, code, and databases are open source!

Now, on with the variables:

| ID | Measurement Procedure Idea | New Indicators |

| CM–SRA-1 | Retrieving the date of the first bug for each member of the community, we are able to know if the number of new member reporting bugs remains stable | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM–SRA-2 | Retrieving the date of the first commit for each member of the community, we are able to know if the number of new member committing remains stable | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM-SRA-3 | CVSAnalY: looking for the first commit of each detected committer in the SCM whose commit is not a code commit (for instance, ignoring source code extensions. MLS: Each new email address detected and its monthly evolution. Bicho: We measure monthly the first bug submitted by registered people. Retrieving the evolution of the first event in the community by a person and if it remains stable, can give an idea of how it evolves, and how many people are coming inside the community. | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM-SRA-4 | Check the core group of developers (those with the 80% of the commits). Now check the first commit of each new member who starts working on the core group. Retrieving this information gives an estimator of how the core contributors is evolving. Thus, we can see if there is a natural regeneration of core developers. | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM-SRA-5 | Core Team = people with the 80% of the commits. After this, any number of people who disappears from this core team is counted as one. Taking into account this metric we can estimate if there is a dramatic decrease in the number of core developers, and so, a risk in the regeneration. | Green: There are no members leaving the project Yellow: There are some people leaving the project, one or two each year Red: A high number of people leave the project. The evolution shows an increase or even a stable period. Black: The number of people leaving the project is extremely high. |

| CM-SRA-6 | Number of people who left the core team minus number of new members of the core team. Monthly analysis. | Green: The balance shows an increase in the number of people coming to the project Yellow: The balance is equal to 0 Red: The balance shows an increase in the number of people leaving the project Black: The balance shows a really high number of people leaving the project |

| CM-SRA-7 | Average age of people working on a project. This metric is focused on the average of years worked by each developer. With this approximation, we are able to know of members are approaching this limit and we can estimate future effort needs. | Green: The longevity is older than 3 years Yellow: The longevity is older than 2 years and younger than 3 years Red: The longevity is older than 1 year and younger than 2 years Black: The longevity is younger than 1 year |

| CM-SRA-8 | Evolution of people who contribute to the source code and reporting bugs. A way to retrieve this data is to analyze those committers and reporters with the same nickname. | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM-SRA-9 | Same metric than above, but this is the sum of all of them, and not the evolution. General number. We can measure the size of a community. | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM-IWA-1 | An event is defined as any kind of activity measurable from a community. Generally speaking, posts, commits or bug reports. Monthly analysis will provide a general view of the project and its tendency. | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM-IWA-2 | Monthly analysis will provide a general view of the project. In this way an increase or decrease in the number of commits will show the tendency of the community | Taking into account the slope of the resultant line (y=mx+b) while measuring the aggregated number and periods of one year: Green: if m > 0 Yellow: if m=0 Red: if m<0 Black if there are no new submitters for several periods |

| CM-IWA-3 | Number of people working on old releases, out of total work on the project. We can determine how supported are the old releases for maintenance purposes. | Green: More than 10% Yellow: Between 5% and 10% Red: Between 0% and 5% Black: Nobody |

| CM-IWA-4 | Looking at the number of committers per each file. This metric shows the territoriality in a project. Generally speaking, most of the files are touched or handled by just one committers. It means that high levels of orphaning may be seen as a risk situation. If a developer leaves the project, her knowledge will disappear and all her files are totally unknown by the rest of the developers team. | Green: Less than 50% of the files are handled by just one committer Yellow: More than 50% of the files are handled by just one committer Red: More than 70% of the files are handled by just one committer Black: More than 90% of the files are handled by just one committer |

| CM-IWA-5 | Number of people working on the project, out of number of people working on the whole project and taking into account the whole set of activities to carry on. High number of SLOC, e-mails or bugs to be fixed per active developer may mean that they are overworked. In this case, the community is clearly busy and they need more people to help on it. | Green: Less than 30.000 Lines per committer and less than 25 bugs per committer Yellow: Between 30.000 and 50.000 lines per committer and between 25 and 75 bugs per committer. Red: Between 50.000 and 100.000 lines per committer and between 75 and 150 bugs per committer Black: More than 100.000 lines per committer and more than 150 bugs per committer |

| CM-IWA-6 | Relationship between committers and total number of lines or files. With this absolute number, we are able to check the number of lines per committer. Thus, just regarding to the source code, we can say if they need more resources on it. | Green: Less than 30.000 Lines per committer Yellow: Between 30.000 and 50.000 lines per committer Red: Between 50.000 and 100.000 lines per committer Black: More than 100.000 lines per committer |

| CM-IWA-7 | Knowledge of the current team about the whole source code, measured in number of files touched by all committers out of the total number of files. This metric gives an approximation of the number of files touched by the whole set of active committers. High percentages will show a high level of knowledge of the current developer team over the whole set of files. | Green: Less than 50 files Yellow: Between 50 and 200 files Red: Between 200 and 500 files Black: More than 500 files per committer |

(CVSanaly, Bicho, MLS are some of the tools that extract information from the various databases that we keep for every project; so for multidimensional data we extract variables from more than one source).

The evaluation becomes quite simple: if there is any red or black metric, you are looking at a high risk project, because there is a significant part of the code managed by a single, or a very small, group of people. We will estimate the number of yellow parameters that can be associated with a medium risk project by comparing our previous QSOS estimates with the new ones; it will be published directly in the guide.

As a side note: I am really grateful for the many researchers that are sending me their works within other open-source related EU projects; after all, we are all working for opennness ![]()

Random thoughts: TomTom, Alfresco

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on March 31st, 2009

Just a quick note on two relevant events in this beginning of week, first the TomTom settlement and the change in strategy of Alfresco (moving to an “open core” strategy).

As for TomTom: I am sorry for all the people that believed that the Dutch company could have been turned into a white knight of Linux, but it was clear from the start that the counter-suing was designed to create a level field for negotiation. There could be no CEO that would have fought the patent fight, understanding that in the eventuality of losing the amount of damages and remedial actions would have, effectively, killed the company. And you don’t know in advance what your chances are, and this is really one of the most dangerous aspects of patents. As for those that claimed that the FAT32 specification was effectively public, the reality is that courts rejected the patents on the original FAT implementation, but not its extensions; and that the “free to use” specification of FAT32 released by Microsoft are limited to the following areas:

“(e) Each of the license and the covenant not to sue described above shall not extend to your use of any portion of the Specification for any purpose other than (a) to create portions of an operating system (i) only as necessary to adapt such operating system so that it can directly interact with a firmware implementation of the Extensible Firmware Initiative Specification v. 1.0 (“EFI Specification”); (ii) only as necessary to emulate an implementation of the EFI Specification; and (b) to create firmware, applications, utilities and/or drivers that will be used and/or licensed for only the following purposes: (i) to install, repair and maintain hardware, firmware and portions of operating system software which are utilized in the boot process; (ii) to provide to an operating system runtime services that are specified in the EFI Specification; (iii) to diagnose and correct failures in the hardware, firmware or operating system software; (iv) to query for identification of a computer system (whether by serial numbers, asset tags, user or otherwise); (v) to perform inventory of a computer system; and (vi) to manufacture, install and setup any hardware, firmware or operating system software.”

So, hardly useable for anything within Linux. At the moment, probably the safest choice would be for embedded vendors to remove the FAT32-specific portions from the code, and use only the traditional 8.3 FAT allocation, eventually extending the use of filesystem-in-file strategy commonly used in games (like ID software’s PAKs).

As for Alfresco: first of all, I wish all the best for Alfresco and their product. It is always one of my favourite examples of successful commercial OSS system, and so I am happy to see that they are getting substantial increases in their turnover (including a nearly doubling of revenue year-over-year). On the other hand I understand perfectly the frustration that “some of the biggest enterprises in the world (and I mean Fortune 50 and even Fortune 10) are only using the open source version of the product”. It seems to me that the choice of what features should be available to enterprise customers vs. open source ones is a good initial choice, and I hope them every possible success. However, I am perplexed: if the OSS Alfresco is doing so well (doubling revenues!) is there really a need for a change in approach? And, given that RedHat is doing quite well, even with CentOS being used in many large scale companies, is it really necessary?

If the need to increase adoption was effectively so strong, I would probably have adopted a timed release for the bug fixes (effectively introducing a RHEL/Fedora like split), and spun off the plugins for connecting to the proprietary systems as a completely different offering; this way, the distinction between what is enterprise and what is open source would be clearer. Anyway: good luck, Alfresco! And continue to be my hero ![]()