Archive for category OSS data

Horses, carriages and cars – the shifting OSS business models, and a proposal

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on June 8th, 2009

If there is a constant in this research area, is the fact that everything is constantly changing. While we debate about whether mixed models are really that important or not, or while free software experts are fighting against brand pollution, I still find amusing the fact that most of what we debate will be probably not relevant in the future at all. Exactly like the initial car models, that resembled the horse-driven carriages that were planning to supplant, some actual OSS business models are half-hearted attempts at bridge the gap between two different worlds, with some advantages and disadvantages of each.

All OSS business models are based on the idea of monetization of a code base, and this monetization can happen in many different steps of the acquisition or use process. Monetization of services, for example, usually happens in the initial adoption step through training and set-up fees, while support monetization happens in the long-term use phase (and in large scale companies tend to be limited in time, as the internal IT staff becomes more and more expert at the infrastructure, and the need for external supports reduces with time); sometimes monetization happens elsewhere (like Mozilla and Google).

Mixed models try to leverage the R&D cost reduction that is inherent in the OSS process, while at the same time maintain the easy and clear proprietary licensing model, where there is a token-based monetization (per CPU, per user, per server, and so on) that is not related to an inherent limitation of the software, but is an artificial barrier introduced to prevent free riding. This, however, introduces the disadvantages of both models into the equation: developers working for a commercial company are reluctant to participate in a project that has a clear potential for third party exploitation, while non-employed developers may be more interested in contributing to more “libre” projects. On the adopter side, the user is not allowed to experiment with the full version of the software, and may not be interested enough in trying the OSS version if the difference in terms of stability and features is too high.

That explains why mixed-model vendors claim that basically no one contributes code to their project (thus neglecting all the non-code contributions, that in some cases are significant), while vendors that select alternative monetization approaches seem to fare better. Pure OSS products are in fact more efficient (and tend to allow for higher company competitiveness), and even vendor-backed projects like Eclipse receive significant external contributions (IBM has only 25% of the active committers, for example).

About the claims that mixed models or open core approaches are the norm, I still stand on my numbers, that shows that less than 25% of the companies use this approach to monetization. Also, the companies are adopting a more softer stance on open core; while a few years ago the code available under the non-OSS license was a substantial part of the functionality of the full product, now the vendors are using many separate non-functional product areas and put them together to create the proprietary product, like certification, stability assurance, official support and sometimes additional code for ancillary activities like monitoring and high-end features like clustering (Alfresco recently announced such a change).

As the horse, carriage and cars example I made at the beginning of this post, I believe that these are steps taken in trying to approach and adopt the optimal model; in this sense, I believe that a better approach is to clearly divide the “core” and “non-core” groups into separate legal entities, with differentiated governance models. In particular, I believe that a more efficient approach is:

- To have a core, Eclipse-like consortia that provide clear, public, transparent management of the central open source part of the project. As for Eclipse, while initially the vendor dominates in terms of contribution, after a while (and in the presence of a healthy external ecosystem) contributions start to reduce the R&D cost – in the case of Eclipse, over 75% of the code commits are from outside IBM.

- To have a separate, independent unit/company that provides, under a traditional proprietary license, the stabilized/extended software without any confusion about what is open source and what is not. It will not be “mixed model”, “commercial OSS” or whatever – just proprietary software. Or, if the offer is service-based, it will be a pure service contract.

I strongly believe that this model can not only put on a rest the entire “mixed model” or open core debate, but can also provide significant productization benefits, by reducing the contribution barrier that so many OSS vendors are experiencing right now. By creating an ecosystem of “development consortia” it will also be possible to increase coordination opportunities, that are sometimes stifled by OSS vendors that pursue independent agendas; it will also reduce customer confusion about what actually they buy when they receive an offer from such a vendor.

Economic Free Software perspectives

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on May 4th, 2009

“How do you make money with Free Software?” was a very common question just a few years ago. Today, that question has evolved into “What are successful business strategies that can be implemented on top of Free Software?”

This is the beginning of a document that I originally prepared as an appendix for an industry group white paper; as I received many requests for a short, data-concrete document to be used in university courses on the economics of FLOSS, I think that this may be useful as an initial discussion paper. A pdf version is available here for download. Data and text was partially adapted from the results of the EU projects FLOSSMETRICS and OpenTTT (open source business models and adoption of OSS within companies), COSPA (adoption of OSS by public administrations in Europe), CALIBRE and INES (open source in industrial environments). I am indebted with Georg Greve of FSFE, that wrote the excellent introduction (more details on the submission here), and that kindly permitted redistribution. This text is licensed under CC-by-SA (attribution, sharealike 3.0) . I would grateful for an email to indicate use of the text, as a way to keep track of it, at cdaffara@conecta.it.

Free Software (defined 1985) is defined by the freedoms to use, study, share, improve. Synonyms for Free Software include Libre Software (c.a. 1991), Open Source (1998), FOSS and FLOSS (both 200X). For purposes of this document, this usage is synonymous with “Open Source” by the Open Source Initiative (OSI).

Economic Free Software Perspectives

Introduction

“How do you make money with Free Software?” was a very common question just a few years ago. Today, that question has evolved into “What are successful business strategies that can be implemented on top of Free Software?” In order to develop business strategies, it is first necessary to have a clear understanding of the different aspects that you seek to address. Unfortunately this is not made easier by popular ambiguous use of some terms for fundamentally different concepts and issues, e.g. “Open Source” being used for a software model, development model, or business model.

These models are orthogonal, like the three axes of the three-dimensional coordinate system, their respective differentiators are control (software model), collaboration (development model), revenue (business model).

The software model axis is the one that is discussed most often. On the one hand there is proprietary software, for which the vendor retains full control over the software and the user receives limited usage permission through a license, which is granted according to certain conditions. On the other hand there is Free Software, which provides the user with unprecedented control over their software through an ex-ante grant of irrevocable and universal rights to use, study, modify and distribute the software.

The development model axis describes the barrier to collaboration, ranging from projects that are developed by a single person or vendor to projects that allow extensive global collaboration. This is independent from the software model. There is proprietary software that allows for far-reaching collaboration, e.g. SAP with it’s partnership program, and Free Software projects that are developed by a single person or company with little or no outside input.

The business model axis describes what kind of revenue model was chosen for the software. Options on this axis include training, services, integration, custom development, subscription models, “Commercial Off The Shelve” (COTS), “Software as a Service” (SaaS) and more.

These three axes open the space in which any software project and any product of any company can freely position itself. That is not to say all these combinations will be successful. A revenue model based on lock-in strategies with rapid paid upgrade cycles is unlikely to work with Free Software as the underlying software model. This approach typically occurs on top of a proprietary software model for which the business model mandates a completed financial transaction as one of the conditions to grant a license.

It should be noted that the overlap of possible business models on top of the different software models is much larger than usually understood. The ex-ante grant of the Free Software model makes it generally impossible to attach conditions to the granting of a license, including the condition of financial transaction. But it is possible to implement very similar revenue streams in the business model through contractual constructions, trademarks and/or certification.

Each of these axes warrants individual consideration and careful planning for the goals of the project. If, for instance the goal is to work with competitors on a non-differentiating component in order to achieve independence from a potential monopolistic supplier, it would seem appropriate to focus on collaboration and choose a software model that includes a strong Copyleft licence. The business model could potentially be neglected in this case, as the expected return on investment comes in the form of strategic independence benefits, and lower licence costs. In another case, a company might choose a very collaborative community development model on top of a strong Copyleft licence, with a revenue model based on enterprise-ready releases that are audited for maturity, stability and security by the company for its customers. The number of possible combinations is almost endless, and the choices made will determine the individual character and competitive strengths and weaknesses of each company. Thinking clearly about these parameters is key to a successful business strategy.

Strategic use of Free Software vs. Free Software Companies

According to Gartner, usage of Free Software will reach 100 percent by November 2009. That makes usage of Free Software a poor criterion for what makes a Free Software company. Contribution to Free Software projects seems a slightly better choice, but as many Free Software projects have adopted a collaborative development model in which the users themselves drive development, that label would then also apply to companies that aren’t Information Technology (IT) companies.

IT companies are among the most intensive users of software, and will often find themselves as part of a larger stack or environment of applications. Being part of that stack, their use of software not only refers to desktops and servers used by the company’s employees, but also to the platform on top of which the company’s software or solution is provided.

Maintaining proprietary custom platforms for a solution is inefficient and expensive, and depending upon other proprietary companies for the platform is dangerous. In response, large proprietary enterprises have begun to phase out their proprietary platforms and are moving towards Free Software in order to leverage the strategic advantages provided by this software model for their own use of software on the platform level. These companies will often interact well with the projects they depend upon, contribute to them, and foster their growth as a way to develop strategic independence as a user of software.

What makes these enterprises proprietary is that for the parts where they are not primarily users of software, but suppliers to their downstream customers, the software model is proprietary, withholding from its customers the same strategic benefits of Free Software that the company is using to improve its own competitiveness.

From a customer perspective, that solution itself becomes part of the platform on which the company’s differentiating activities are based. This, as stated before, is inefficient, expensive and a dangerous strategy.

Assuming a market perspective, it represents an inefficiency that provides business opportunity for other companies to provide customers with a stack that is Free Software entirely, and it is strategically and economically sane for customers to prefer those providers over proprietary ones for the very same reasons that their proprietary suppliers have chosen Free Software platforms themselves.

Strategically speaking, any company that includes proprietary software model components in its revenue model should be aware that its revenue flow largely depends upon lack of Free Software alternatives, and that growth of the market, as well as supernatural profits generated through the proprietary model both serve to attract other companies that will make proprietary models unsustainable. When that moment comes, the company can either move its revenue model to a different market, or it has to transform its revenue source to work on top of a software model that is entirely Free Software.

So usage of and contribution to Free Software are not differentiators for what makes a Free Software company. The critical differentiator is provision of Free Software downstream to customers. In other words: Free Software companies are companies that have adopted business models in which the revenue streams are not tied to proprietary software model licensing conditions.

Economic incentives of Free Software adoption

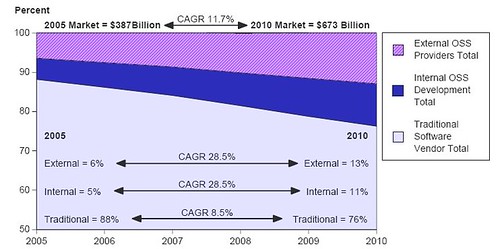

The broad participation of companies and public authorities in the Free Software market is strictly related to an economic advantage; in most areas, the use of Free Software brings a substantial economic advantage, thanks to the shared development and maintenance costs, already described by researchers like Gosh, that estimated an average R&D cost reduction of 36%. The large share of “internal” Free Software deployments explains why some of the economic benefits are not perceived directly in the business service market, as shown by Gartner:

Gartner predicts that within 2010 25% of the overall software market will be Free Software-based, with rougly 12% of it “internal” to companies and administrations that adopt Free Software. The remaining market, still substantial, is based on several different business models, that monetize the software using different strategies.

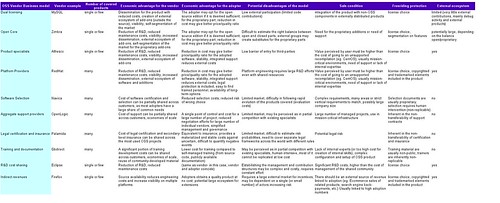

A recent update (february 2009) of the FLOSSMETRICS study on Free Software-based business model is presented here, after an analysis of more than 200 companies; the main models identified in the market are:

- Dual licensing: the same software code distributed under the GPL and a proprietary license. This model is mainly used by producers of developer-oriented tools and software, and works thanks to the strong coupling clause of the GPL, that requires derivative works or software directly linked to be covered under the same license. Companies not willing to release their own software under the GPL can obtain a proprietary license that provides an exemption from the distribution conditions of the GPL, which seems desirable to some parties. The downside of dual licensing is that external contributors must accept the same licensing regime, and this has been shown to reduce the volume of external contributions, which are limited mainly to bug fixes and small additions.

- Open Core (previously called “split Free Software/proprietary” or “proprietary value-add”): this model distinguishes between a basic Free Software and a proprietary version, based on the Free Software one but with the addition of proprietary plug-ins. Most companies following such a model adopt the Mozilla Public License, as it allows explicitly this form of intermixing, and allows for much greater participation from external contributions without the same requirements for copyright consolidation as in dual licensing. The model has the intrinsic downside that the Free Software product must be valuable to be attractive for the users, i.e. it should not be reduced to “crippleware”, yet at the same time should not cannibalise the proprietary product. This balance is difficult to achieve and maintain over time; also, if the software is of large interest, developers may try to complete the missing functionality in Free Software, thus reducing the attractiveness of the proprietary version and potentially giving rise to a full Free Software competitor that will not be limited in the same way.

- Product specialists: companies that created, or maintain a specific software project, and use a Free Software license to distribute it. The main revenues are provided from services like training and consulting (the “ITSC” class) and follow the original “best code here” and “best knowledge here” of the original EUWG classification [DB 00]. It leverages the assumption, commonly held, that the most knowledgeable experts on a software are those that have developed it, and this way can provide services with a limited marketing effort, by leveraging the free redistribution of the code. The downside of the model is that there is a limited barrier of entry for potential competitors, as the only investment that is needed is in the acquisition of specific skills and expertise on the software itself.

- Platform providers: companies that provide selection, support, integration and services on a set of projects, collectively forming a tested and verified platform. In this sense, even GNU/Linux distributions were classified as platforms; the interesting observation is that those distributions are licensed for a significant part under Free Software licenses to maximize external contributions, and leverage copyright protection to prevent outright copying but not “cloning” (the removal of copyrighted material like logos and trademark to create a new product)1. The main value proposition comes in the form of guaranteed quality, stability and reliability, and the certainty of support for business critical applications.

- Selection/consulting companies: companies in this class are not strictly developers, but provide consulting and selection/evaluation services on a wide range of project, in a way that is close to the analyst role. These companies tend to have very limited impact on the Free Software communities, as the evaluation results and the evaluation process are usually a proprietary asset.

- Aggregate support providers: companies that provide a one-stop support on several separate Free Software products, usually by directly employing developers or forwarding support requests to second-stage product specialists.

- Legal certification and consulting: these companies do not provide any specific code activity, but provide support in checking license compliance, sometimes also providing coverage and insurance for legal attacks; some companies employ tools for verify that code is not improperly reused across company boundaries or in an improper way.

- Training and documentation: companies that offer courses, on-line and physical training, additional documentation or manuals. This is usually offered as part of a support contract, but recently several large scale training center networks started offering Free Software-specific courses.

- R&D cost sharing: A company or organization may need a new or improved version of a software package, and fund some consultant or software manufacturer to do the work. Later on, the resulting software is redistributed as open source to take advantage of the large pool of skilled developers who can debug and improve it. A good example is the Maemo platform, used by Nokia in its Mobile Internet Devices (like the N810); within Maemo, only 7.5% of the code is proprietary, with a reduction in costs estimated in 228M$ (and a reduction in time-to-market of one year). Another example is the Eclipse ecosystem, an integrated development environment (IDE) originally released as Free Software by IBM and later managed by the Eclipse Foundation. Many companies adopted Eclipse as a basis for their own product, and this way reduced the overall cost of creating a software product that provides in some way developer-oriented functionalities. There is a large number of companies, universities and individual that participate in the Eclipse ecosystem; as an example:

As recently measured, IBM contributes for around 46% of the project, with individuals accounting for 25%, and a large number of companies like Oracle, Borland, Actuate and many others with percentages that go from 1 to 7%. This is similar to the results obtained from analysis of the Linux kernel, and show that when there is an healthy and large ecosystem the shared work reduces engineering cost significantly; it is estimated that it is possible to obtain savings in terms of software research and development of 36% through the use of Free Software; this is, in itself, the largest actual “market” for Free Software, as demonstrated by the fact that the majority of developers are using at least some Free Software within their own code (56.2%).

As recently measured, IBM contributes for around 46% of the project, with individuals accounting for 25%, and a large number of companies like Oracle, Borland, Actuate and many others with percentages that go from 1 to 7%. This is similar to the results obtained from analysis of the Linux kernel, and show that when there is an healthy and large ecosystem the shared work reduces engineering cost significantly; it is estimated that it is possible to obtain savings in terms of software research and development of 36% through the use of Free Software; this is, in itself, the largest actual “market” for Free Software, as demonstrated by the fact that the majority of developers are using at least some Free Software within their own code (56.2%). - Indirect revenues: A company may decide to fund Free Software projects if those projects can create a significant revenue source for related products, not directly connected with source code or software. One of the most common cases is the writing of software needed to run hardware, for instance, operating system drivers for specific hardware. In fact, many hardware manufacturers are already distributing gratis software drivers. Some of them are already distributing some of their drivers (specially those for the Linux kernel) as Free Software.

The loss-leader is a traditional commercial model, common also outside of the world of software; in this model, effort is invested in a Free Software project to create or extend another market under different conditions. For example, hardware vendors invest in the development of software drivers for Free Software operating systems (like GNU/Linux) to extend the market of the hardware itself. Other ancillary models are for example those of the Mozilla foundation, which obtains a non trivial amount of money from a search engine partnership with Google (an estimated 72M$ in 2006), while SourceForge/OSTG receives the majority of revenues from ecommerce sales of the affiliate ThinkGeek site

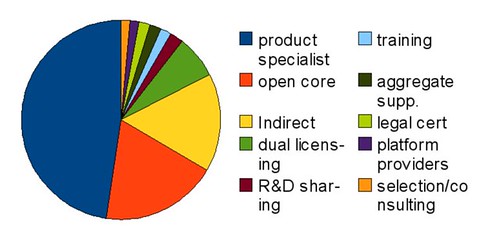

We found (confirming previous research from the 451 group) that at the moment there is no “significant” model, with companies more or less adopting and changing model depending on the specific market or the shifting costs. For example, during 2008 a large number of companies shifted from an “open core” model to a pure “product specialist” one to leverage the external community of contributors.

According to the collected data, among Free Software companies the “Fully Free Software” approach is still prevalent, followed by the “Open Core” and the “Dual Licensing” mode:

| Model name | # companies |

| product specialist | 131 |

| open core | 52 |

| Indirect | 44 |

| dual licensing | 19 |

| R&D sharing | 6 |

| training | 5 |

| aggregate supp. | 5 |

| legal cert | 5 |

| platform providers | 4 |

| selection/consulting | 4 |

Some companies have more than one principal model, and thus are counted twice; in particular, most dual licensing companies are also selling support services, and thus are marked as both. Also, product specialists are counted only when there is a demonstrable participation of the company into the project as “main committer”; otherwise, the number of specialists would be much greater, as some projects are the center of commercial support from many companies (a good example is OpenBravo or Zope).

Another relevant consideration is the fact that platform providers, while limited in number, tend to have a much larger revenue rate than both specialists or open core companies.

Many researchers are trying to identify whether there is a more “efficient” model among all those surveyed; what we found is that the most probable future outcome will be a continuous shift across model, with a long-term consolidation of development consortia (like Symbian and Eclipse) that provide strong legal infrastructure and development advantages, and product specialists that provide vertical offerings for specific markets. This contrasts with the view that, for example, “mixed” models provide an inherent advantage; for example, Matthew Aslett of the 451 group (one of the leading researchers in Free Software business models) wrote:

“The Open-Core approach is mostly (though not exclusively) used by vendors that dominate their own development communities. While this provides benefits in terms of controlling the direction of development and benefiting from the open source distribution model there are also risks involved with promoting and managing community development – or not. In fact, many of these companies employ the majority of the developers on the project, so they are actually missing out on many of the benefits of the open source development model (more eyeballs, lower costs etc).

Additionally, by providing revenue-generating features on top of open source code, Open-Core vendors are attempting to both disrupt their segment and profit from that disruption. I previously argued that “it is probably easier in the long-term to generate profit from adjacent proprietary products than it is to generate profit from proprietary features deployed on top of the commoditized product.”

While Open-Core is definitely the commercial open source strategy of the day and is effective in building the revenue growth required to fuel an exit strategy, I have my doubts as to whether it is sustainable in the long-term due to a combination of the issues noted above.”

The fact that Free Software is in a sense a non-rival good also facilitates cooperation between companies, both to increase the geographic base and to be able to engage large scale contracts that may require multiple competencies. Three main collaboration strategies were identified among smaller companies: geographical (same product or service, different geographical areas); “vertical” (among products) or “horizontal” (among activities). Geographic cooperation is simpler, and tends to be mainly service-based; an example is the Zope Europe Association, that unites many service providers centered on specific Zope and Plone expertise. Vertical cooperation is done by companies that performs an integrated set of activities on one or more packages. Multiple vendors with overlapping products can collaborate on a single offer (eg. operating system and Groupware), that may form a more interesting or complete offer for the selected customer segment.

The summary table is available here along with a rationale for the categories used; linked below to a public Google docs document:

Bibliography:

[451 08]The 451 group, Open source is not a business model.

[Car 07]Carbone, P. Value Derived from Open Source is a Function of Maturity Levels, OCRI conference “Alchemy of open source businesses”, 2007

[DB 00]Daffara, C. Barahona, J.B. Free Software/Open Source: Information Society Opportunities for Europe? working paper

[Daf 06]Daffara, C. Sustainability of FLOSS-based business models, II Open Source World Conference, Malaga 2006

[Daf 06-2]Daffara, C. Introducing open source in industrial environments. 3rd CALIBRE workshop

[Daf 07]Daffara, C. Business models in OSS-based companies. OSSEMP workshop, Third international conference on open source. Limerick 2007

[ED 05]Evans Data, Open Source Vision report, 2005

[Gar 06]Gartner Group, Open source going mainstream. Gartner report, 2006

[Gosh 06]Gosh, et al. Economic impact of FLOSS on innovation and competitiveness of the EU ICT sector.

[IDC 06]IDC, Open Source in Global Software: Market Impact, Disruption, and Business Models. IDC report, 2006

[Jul 06]Jullien N. (ed) New economic models, new software industry economy. RNTL report

[VH 03]Von Hippel, E. and G. von Krogh, Open Source Software and the “Private-Collective” Innovation Model: Issues for Organizational Science. Organization Science, 2003. 14(2): p. 209-223

[VH 05]Von Hippel, E. Democratizing innovation. MIT press, 2005

Helping OSS adoption in public administrations: some resources

Posted by cdaffara in OSS adoption, OSS business models, OSS data on April 30th, 2009

It was a busy and happy week, and among the many things I received several requests for information on how to facilitate adoption of OSS by public administrations. After the significant interest of a few years ago, it seems that the strong focus on “digital citizenship” and the need to increase interoperability with other administrations is pushing OSS again (and the simplification, thanks to the reduction in procurement hurdles, also helps). I have worked in this area for some years, first in the SPIRIT project (open source for health care), then in the COSPA and OpenTTT projects, that were oriented towards facilitating OSS adoption. I will try to provide some links that may be useful for administrations looking to OSS:

- Let’s start with requirement analysis. What is important, what is not, and how to prioritize things was one of the arguments discussed in COSPA, and two excellent deliverables were produced (maybe a bit theoretical, but you can skip the boring parts): analysis of requirements for OS and ODS and prioritization of requirements (both pdf files).

- As part of our guide in the FLOSSMETRICS project we have a list of best practices, that may be useful; in general, the guide does have some more material from various European projects. I would like to thank PJ from Groklaw, that hosted my work for discussion there, and to the many groklawers that helped in improving it.

- One of the best migration guide ever created, by the Germany Ministry of the Interior (KBST), is available in english (pdf file). It covers many practical problems, server and desktop migrations, project planning, legal aspects (like changing contractual relations with vendors), evaluation of economics and efficiency aspects and much more. Unfortunately the 2.1 edition is still not available in english…

- For something simpler, some guidance and economic comparison from the Treasury board of Canada;

- and a very detailed desktop migration redbook from IBM.

- The European Open Source Observatory does have a long and interesting list of case studies, both positive and negative (so the reader can get a balanced view).

And now for some additional comment, based on my personal experience:

- A successful OSS migration or adoption is not only a technical problem, but a management and social problem as well. A significant improvement in success rates can be obtained simply by providing a simple, 1 hour “welcoming” session to help users in understanding the changes and the reasons behind it (as well as providing some information on OSS and its differences with proprietary software).

- In most public administrations there are “experts” that provide most of the informal IT help; some of those users may felt threatened by the change of IT infrastructure, as it will remove their “skill advantage”. So, a simple and effective practice is to search for them and for passionate users and enlist them as “champions”. Those champions are offered the opportunity for further training and additional support, so they can continue in their role without disruptions.

- Perform a real cost analysis of the actual, proprietary IT infrastructure: sometimes huge surprises are found, both in contractual aspects and in actual costs incurred that are “hidden” under alternative balance voices.

- If a migration requires a long adaptation time, make sure that the management remains the same for the entire duration, or that the new management understands and approves what was done. One of the most sad experiences is to see a migration stop halfways because the municipality coalition changes, and the new coalition has no understanding of what was planned and why (“no one remembers the reasons for the migration” was one of the phrases that I heard once).

- Create an open table between local administrations: sometimes you will find someone that already is using OSS and simply told no one. We had a local health agency that silently swapped MS Office with OpenOffices in the new PCs for hospital workers, and nobody noticed

- Have an appropriate legislative policy: informative campaigns and mandatory adoption are the two most efficient approaches to create OSS adoption, while subsidization has a negative welfare effect: “We show that a part from subsidization policies, which have been proved to harm social surplus, supporting OSS through mandatory adoption and information campaign may have positive welfare effects. When software adoption is affected by strong network effects, mandatory adoption and information campaign induce an increase in social surplus” (Comino, Manenti, “Free/Open Source vs Closed Source Software: Public Policies in the Software Market”). Also, in the TOSSAD conference proceedings, Gencer, Ozel, Schmidbauer, Tunalioglu, “Free & Open Source Software, Human Development and Public Policy Making: International Comparison”.

- Check for adverse policy effects: In one of my case studies I found a large PA that was forced back to commercial software, because the state administration was subsidizing only the cost of proprietary software, while OSS was considered to be “out of procurement rules” and thus not paid for. This does also have policy implications, and require a careful choice of budget voices by the adopters administration.

We found that by presenting some “exemplar” OSS projects that can be used immediately, the exploration phase usually turns into a real adoption experiment. The tool that I use as an introduction are:

- Document management: Alfresco. It is simple to install, easy to use and with good documentation, and can be introduced as a small departmental alternative to the “poor man repository”, that is a shared drive on the network. Start with the file system interface, and show the document previews and the search functionalities (more complex activities, like workflow, can be demonstrated in a second time). Nuxeo is also a worthy contender.

- Groupware: my personal favorite, Zimbra, that can provide everything that Exchange does, and has a recently released standalone desktop client that really is a technical marvel. If you are still forced into Outlook you can use Funambol (another OSS gem) that with a desktop client can provide two-way synchronization with Outlook, exactly like Exchange.

- Project management: a little known project from Austria is called OnePoint, and does have a very well designed web and native interface for the traditional project management tasks.

- Workstation management: among the many choices, if (as it usually happens) the majority of the desktops are Windows-based there is a long-standing german project called Opsi, that provides automatic OS install, patch management, HW&SW inventory and much more.

Of course there are many other tools, but by presenting an initial, small subset it is usually possible to raise the PA interest in trying and testing out more. For some other software packages, you can check the software catalog that we provided as part of our FLOSSMETRICS guide. I will be happy to answer to individual requests for software that will be posted as comments to this articles, or sent to me by twitter (@cdaffara); if there are enough interest, I will prepare a follow-up post with more tools.

Sorry, not right. An answer to Raymond’s post on the GPL

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on April 27th, 2009

I read with great interest the post by Eric Raymond on the GPL and efficiency, “The Economic Case Against the GPL“; because economic aspects of OSS are my current main research work (well, up to the end of FLOSSMETRICS, then I’ll find something new ![]() ) The main argument is nicely summarized in the first lines: “Is open-source development a more efficient system of software production than the closed-source system? I think the answer is probably “yes”, and that it follows the GNU GPL is probably doing us more harm than good.”. Easy, clear, and totally wrong.

) The main argument is nicely summarized in the first lines: “Is open-source development a more efficient system of software production than the closed-source system? I think the answer is probably “yes”, and that it follows the GNU GPL is probably doing us more harm than good.”. Easy, clear, and totally wrong.

The post clearly distinguish between the “ethical” aspects of the GPL with the interaction model that is enforced by the GPL redistribution clause; ESR briefly describes a ideal world where:

“If we live in “Type A” a universe where closed source is more efficient, markets will eventually punish people who take closed source code open. Markets will correspondingly reward people who take open source closed. In this kind of universe, open source is doomed; the GPL will be subverted or routed around by efficiency-seeking investors as surely as water flows downhill.If we live in a “Type B” universe where open source is more efficient, markets will eventually punish people who take open source code closed. Markets will correspondingly reward people who take closed source open. In such a universe closed source is its own punishment; open source will capture ever-larger swathes of industry as investors chase efficiency gains.”

So, Raymond concludes, the GPL is either unnecessary or worse anti-economical. The problem lies in the assumption that the market is static, that the end equilibrium will always be optimal, that imbalances in the market are not relevant (only the end result is), and so on. I will start with the easy ones:

- the market is NOT static. The fact that one production model is (or is not) more efficient is something that can be modelled easily, but is not really relevant when all agents are able to change their own interaction model at will. Many researchers demonstrated for example that in a simple, two-actor market (one OSS and one proprietary), even in the assumption that OSS is superior in every aspect there are situation where the pre-existing network effect will actually be able to extinguish OSS as soon as there is sufficient pricing discretionality by the proprietary vendor.

- End equilibrium in real-life markets are not always optimal: the existence of monopolies is the most visible example of this fact (and the fact that there is a company that has been found guilty of multiple abuse of monopoly markets should make this clear).

- The process is as important as the end result: you can become rich after a life of poverty (and receive all your money your last day of life) or have a generally well-off life, constantly increasing and spending what you obtain. What life do you prefer? So, among all the paths that lead to an OSS (in this case, a FLOSS) world, the one that enforces in a constant way an increase of the FLOSS component is preferable to one that, in an hypothetical way, will lead in the end to market domination.

In general, of all the aspects of OSS that are interesting (and there are many), I find the GPL family of licenses as the brightest examples of law engineering, and I believe that a substantial reason for the successes of OSS are dependent on it. Of course, there are other economical aspects that are relevant, and I agree with the fact that OSS is in general more efficient (as I wrote here, here and here). I disagree with both the premise and the conclusions, however, as I believe that the set of barriers created by the GPL are vital to create a sustainable market here and now, and not in an hypotetical future.

The procurement advantage, or a simple test for “purity”

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on April 20th, 2009

There is no end in sight for the “open core” debate, or for the matter what role companies should have in the OSS marketplace. We recently witnessed the lively debated sparked by a post by James Dixon, that quickly prompted Tarus Balog to descent into another of his informed and passionate posts on open core and OSS. This is not the first (and will not be the last) of public discussions on what an OSS vendor is, and I briefly entered the fray as well. I am quite sure that this discussion will actually continue for a long time, just lowering its loudness and turning into the background as OSS becomes more and more entrenched inside of our economy.

There is, however, a point that I would like to make about the distinction between “pure OSS” and “open core” licensing, a point that does not imply any kind of “ethical” or “purity” measure, but just a consideration on economics. When we consider what OSS is and what advantage it brings to the market, it is important to consider that a commercial OSS transaction usually has two “concrete” partners: the seller (the OSS vendor) and the buyer, that is the user. If we look at the OSS world we can see that in both the pure and the open core model the vendor has the added R&D sharing cost reduction (that, as I wrote about in the past, can provide significant advantages). But R&D is not the only advantage: the reality is that “pure” OSS has a great added advantage for the adopter, that is the greatly reduced cost and effort of procurement.

With OSS the adopter can scale a single installation company-wide without a single call to the legal or procurement departments, and it can ask support from the OSS vendor if needed- eventually after the roll-out has been performed. With open core, the adopter is not allowed to do the same thing, as the proprietary extensions are not under the same license of the open source part; so, if you want to extend your software to more servers, you are forced to ask the vendor- exactly the same of proprietary software systems. This is, in fact, a much overlooked advantage of OSS, that is especially suited to those “departmental” installations that would be probably prohibited if legal or acquisition department would have to be asked for budget.

I believe that this advantage is significant and largely hidden. I started thinking about it while helping a local public administration in the adoption of an OSS-based electronic data capture for clinical data, and discovered that for many authorities and companies procurement (selecting the product, tendering, tender evaluation, contracting, etc.) can introduce many months in delays, and substantially increase costs. For this reason, we recently introduced with our customers a sort of “quick test” for OSS purity:

The acquired component is “pure OSS” if (eventually after an initial payment) the customer is allowed to perform extensions to its adoption of the component inside and outside of its legal border without the need for further negotiation with the vendor.

The reason for that “eventually after an initial payment” because the vendor may decide to release the source code only to customers (this is something that is allowed by some licenses), and the “inside and outside of its legal border” is a phrase that explicitly includes not only redistribution and usage within a single company, but also to external parties that may be not part of the same legal entity. This distinction may not be important for small companies, but may be vital for example for public authorities that need to redistribute a software solution to a large audience of participating public bodies (a recent example I found is a regional health care authority, that is exploring an OSS solution to be distributed to hospital, medical practitioners and private and public structures). Of course, this does not imply that the vendor is forced to offer services in the same way (services and software are in this sense quite distinct) or that the adopter should prefer “pure OSS” over “open core” (in fact, this is not an expression of preference for one form over the other).

We found this simple test to be useful especially for those new OSS adopters that are not overly interested in the intricacies of open source business models, and makes for a good initial question to OSS vendors to understand what are the implication of acquiring a pure vs. an open core solutions.

A brief research summary

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on April 17th, 2009

After two months and 24 posts, I would like to thank all the kind people that mentioned our FLOSSMETRICS and OpenTTT work, especially Matthew Aslett, Matt Asay, Tarus Balog, Pamela Jones and many others with which I had the pleasure to exchange views with. I received many invaluable suggestions, and one of the most common one was to have a small “summary” of the posted research, as a landing page. So, here is a synthesis of the previous research posts:

- Why use OSS in product development: a set of examples from a thesis by Erkko Anttila, “Open Source Software and Impact on Competitiveness: Case Study” from Helsinki University of Technology, that provided hard data on the different hybrid community/company approaches by Nokia and Apple, and the relative gains and advantages.

- The dynamics of OSS adoption – 1: an initial view on the different dynamics behind open source adoption, starting with diffusion processes. Some data was also presented on unconstrained monetization.

- On business models and their relevance: A follow-up post on work by Matthew Aslett, introducing my view that future OSS business models will see more industry consortia and specialists, as more and more groups start to take advantage of the collaborative model, and will need more coordination on how to contribute back.

- Transparency and dependability for external partners: Outlining the transparency advantages of most OSS projects (with two examples mentioned: Zimbra and Alfresco) and the added advantage for partners, that can synchronize their work with that of the OSS community.

- The dynamics of OSS adoptions, II – diffusion processes: A presentation of diffusion processes as one of the models in OSS adoption, and a presentation of the UTAUT model for estimating the degree of acceptance of OSS.

- From theory to practice: the personal desktop linux experiment: A (long) example on how to apply the previously discussed models in a theoretical exercise: creating an end-user, large scale linux PC for personal activities. The post was inspired by work done during the Manila workshop along with UN’s International Open Source Network for facilitating take-up of open source by south-east Asean SMEs.

- Rethinking OSS business model classifications by adding adopters’ value: A presentation of the new classification of OSS business models; I have to thank Matthew Aslett of the 451 group for the many comments, and for accepting to share his work from the CAOS report with us.

- Comparing companies effectiveness: a response to Savio Rodrigues: A post written in response to work by Savio Rodrigues, on the relative shares of R&D of OSS companies compared to traditional IT companies.

- Our definitions of OSS-based business models: A follow-up of the “rethinking..” post, it outlines the new definitions of OSS business models created for the final part of the FLOSSMETRICS project.

- Another take on the financial value of open source: Our estimates of the value of the open source software market, and a call for further research on non-code contributions.

- OSS-based business models: a revised study based on 218 companies: A post providing the summary of the extended FLOSSMETRICS study on open source companies, that increased its number from 80 to 218, with some observation on relative size and usage of the various models.

- Estimating savings from OSS code reuse, or: where does the money comes from?: One of my favourite posts, provides a long discussion of the savings obtained when using OSS inside of other products, with some additional data obtained through COCOMO modeling.

- Another data point on OSS efficiency: A short post focusing on data from the italian TEDIS research, that showed how OSS companies are on average more capable to take on larger customers when compared with benchmark IT companies of the same size.

- The new FLOSSMETRICS project liveliness parameters: Fresh from the other project researchers, I provided a list of the new “project liveness” parameters that will be used in the SME guide.

- Reliability of open source from a software engineering point of view: A post that presents some results on how open source tends to be of higher quality under specific circumstances, and a follow-up idea on how this may be due to basic software engineering facts (related to component reuse).

- Open source and certified systems: A post inspired by a recent white paper on e-voting, the post presents my views on high-integrity and life-critical open source systems.

Open source and certified systems

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data on April 16th, 2009

A recent white paper, published by the Election Technology Council (an industry trade association representing providers for over 90% of the voting systems used in the United States), analyses the potential role of open source software in voting systems, concludes that “it is.. premature. Given the economic dynamics of the marketplace, state and federal governments should not adopt unfair competitive practices which show preferential treatment towards open source platforms over proprietary ones. Legislators who adopt policies that require open source products, or offer incentives to open source providers, will likely fall victim to a perception of instituting unfair market practices.” (where do I have heard this? curious, sometimes, the deja vu feeling…)

The white paper however does contain some concepts that I have found over and over, the result of mixing the “legal” perspective of OSS (the license on which the software is released) with the “technical” aspects (the collaborative development model), arriving at some false conclusions that are unfortunately shared by many others. For this reason, I would like to add my perspective on the issue of “certified” source code and OSS:

- First of all, there is no causal relation between the license aspect and the quality of the code or its certifiability. It is highly ironic that the e-voting companies are complaining of the fact that OSS may be potentially not tested enough for critical environments like voting, given the results of some testing on their own software systems: “the implementation of cryptographic protection is flawed..this key is hard-coded into the source code for the AV-TSx, which is poor security practice because, among other things, it means the same key is used in every such machine in the U.S … and can be found through Google. The result is that in any jurisdiction that uses the default keys rather than creating new ones, the digital signatures provide no protection at all.” “No use of high assurance development methods: The AccuBasic interpreter does not appear to have been written using high-assurance development methodologies. It seems to have been written according to ordinary commercial practices. … Clearly there are serious security flaws in current state of the AV-OS and AV-TSx software” (source: Security Analysis of the Diebold AccuBasic Interpreter, Wagner, Jefferson, Bishop). Of course, there are many other reports and news pieces on the general unreliability of the certified GEMS software, just to pick the most talked about component. The fact is that assurance and certification is a non-functional aspect that is unrelated to the license the software is released with, as certifications of software quality and adherence to high-integrity standards are based on design documents, the adherence to development standards, testing procedures and much more- but not licensing.

- I have already written about our research on open source quality from the software engineering point of view, and in general it can be observed that open source development models tend to have an higher improvement in quality within a specific time frame when compared to proprietary software systems under specific circumstances (like a healthy contributor community).

- It is possible to certify open source systems under the strictest certification rules, like the SABI “secret and below” certification, medical CCHIT, encryption FIPS standard, common criteria Evaluation Assurance Level EAL4+ (and in one case, meet or exceed EAL5), civil engineering (where the product is used for the stability computations for EDF nuclear plants designs), avionics and ground-based high-integrity systems, like air traffic control and railrway systems (we explored the procedures for achieving certified status for pre-existing open source code in the CALIBRE project). Thus, it is possible to meet and exceed the regulatory rules for a wide spectrum of environments with far more stringent specifications than the current e-voting environment.

- It seems that the real problem lies in the potential for competition from OSS voting systems: “over proprietary ones. Legislators who adopt policies that require open source products, or offer incentives to open source providers, will likely fall victim to a perception of instituting unfair market practices. At worst, policy-makers may find themselves encouraging the use of products that do not exist and market conditions that cannot support competition.” The reality is that there are some open source voting software (the white paper even lists some), and the real threat is the government to start funding those projects instead of buying proprietary combinations. This is where the vendors clearly show the underlying misunderstanding on how open source works: you can still sell your assembly of hardware and software (as with EAL, it is the combination of both that is certified, not the software in isolation) and continue the current business model. It is doubtful that the “open source community” (as mentioned in the paper) will ever certify the code, as it is a costly and substantial effort, exactly like no individual applied to EAL4+ certification for Linux (that requires a substantial amount of money).

The various vendors would probably do something better if they started a collaborative effort for a minimum-denominator system to be used as a basis for their system, in a way similar to that performed by mobile phone companies in the LiMo and Android projects, or through industry consortia like Eclipse. They could still be introducing differentiating aspects in the hardware and upper-layer software, while reducing the costs of R&D and improving the transparency of a critical component of our modern democracies.

MXM, patents and licenses: clarity is all it takes

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on April 10th, 2009

Recently on the OSI mailing list Carlo Piana wrote a proposed license for the reference implementation of the ISO/IEC 23006 MPEG eXtensible Middleware (MXM). The license is derived from the MPL with the removal of some of the patent conditions from the text of the original license, and clearly creates a legal boundary conditions that grants patent rights only for those who compile it only for internal purposes without direct commercial exploitation. I tend to agree on Carlo’s comment: “My final conclusion is that if the BSD family is considered compliant, so shall be the MXM, as it does not condition the copyright grant to the obtaining of the patents, just as the BSD licenses don’t deal with them. And insofar an implementer is confident that the part of the code it uses if free from the patented area, or it decided to later challenge the patent in case an infringement litigation is threatened, the license works just fine.” (as a side note: I am completely and totally against software patents, and I am confident that Carlo Piana is absolutely against them as well).

Having worked in the italian ISO JTC1 chapter, I also totally agree with one point: “the sad truth is that if we did not offer a patent-agnostic license we would have made all efforts to have an open source reference implementation moot.” Unfortunately, ISO still believes that patents are something that is necessary to convince companies to participate in standard groups, despite the existence of standard groups that do work very well without this policy (my belief is that the added value of standardization in terms of cost reductions are well worth the cost of participating in the creation of complex standards like MPEG, but this is for another post).

What I would like to make clear is that the real point is not if the proposed MXM license is OSI-compliant or not: the important point is why you want it to be open source. Let’s consider the various alternatives:

- the group believes that an open source implementation may receive external effort, much like the traditional open source projects, and thus reduce maintenance and extension effort. If this is the aim, then the probability of having this kind of external support is quite low, as companies would avoid it (as the license would not allow in any case a commercial use with an associated patent license), and researchers working in the area would have been perfectly satisfied with any kind of academic or research-only license.

- the group wants to increase the adoption of the standard, and the reference implementation should be used as a basis for further work to turn it into a commercial product. This falls in the same cathegory as before; why should I look at the reference implementation, if it does not grant me any potential use? The group could have simply published the source code for the reference, and said “if you want to use it, you should pay us a license for the embedded patents”.

- the group wants to have a “golden standard” to benchmark external implementations (for example, to see that the bitstreams are compliant). Again, there is no need for having an open source license.

The reality is that there is no clear motivation behind making this under an open source license, because the clear presence of patents on the implementation makes it risky or non-free to use for any commercial exploitation. Microsoft, for example, did it much better: to avoid losing their rights to enforce their patents, they paid or supported other companies to create a patent-covered software and released it under an open source license. Since the “secondary” companies do not hold any patent, with the releasing of the code they are not relieving any threat from the original Microsoft IPR, and at the same time they use a perfectly acceptable OSI-approved license.

As the purpose of the group is twofold (increase adoption of the standards, make commercial user pay for the IPR licensing) I would propose a different alternative: since the real purpose is to get paid for the patents, or to be able to enforce them in case of commercial competitors, why don’t you dual-license it with the strongest copyleft license available (at the moment, the AGPL)? This way, any competitor would be forced to be fully AGPL (and so any improvement would have to be shared, exchanging the lost licensing revenue for the maintenance cost reduction) or to pay for the license (turning everything into the traditional IPR licensing scheme).

I know, I know – this is wishful thinking. Carlo, I understand your difficult role…

Another hypocrite post: “Open Source After ‘Jacobsen v. Katzer’”

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, divertissements on April 8th, 2009

The reality is that I am unable to resist. To see a post containing idiotic comments on open source, masqueraded as a serious article, makes me start giggling with “I have to write them something” (my coworkers are used to it – they sometimes comment with “another post is arriving” or something more humorous). The post of today is a nicely written essay from Jonathan Moskin, Howard Wettan and Adam Turkelon Law.com, with the title “Open Source After ‘Jacobsen v. Katzer’”, referring to a recent US Federal Circuit decision. The main point of the ruling is “…the Federal Circuit’s recognition that the terms in an open source license can create enforceable conditions to use of copyrighted materials”; that is, the fact that software licenses (in this case, the Artistic License) that limit redistribution are enforceable. Not only this, but the fact that the enforceability is also transferable: “because Jacobsen confirmed that a licensee can be liable for copyright infringement for violating the conditions of an open source license, the original copyright owner may now have standing to sue all downstream licensees for copyright infringement, even absent direct contractual privity”.

This is the starting point for a funny tirade like: “Before Jacobsen v. Katzer, commercial software developers often avoided incorporating open source components in their offerings for fear of being stripped of ownership rights. Following Jacobsen, commercial software developers should be even more cautious“(the article headline in the Law.com front page) to “It is perhaps also the most feared for its requirement that any source code compiled with any GPL-licensed source code be publicly disclosed upon distribution — often referred to as infection.” (emphasis mine).

Infection??

And the closing points: “Before Jacobsen v. Katzer, commercial software developers already often avoided incorporating open source components in their offerings for fear of being stripped of ownership rights. While software development benefits from peer review and transparency of process facilitated by open source, the resulting licenses, by their terms, could require those using any open source code to disclose all associated source code and distribute incorporated works royalty-free. Following Jacobsen v. Katzer, commercial software developers should be even more cautious of incorporating any open source code in their offerings. Potentially far greater monetary remedies (not to mention continued availability of equitable relief) make this vehicle one train to board with caution.”

Let’s skip the fact that the law practitioners that wrote this jewel of law journalism are part of the firm White & Case that represented Microsoft in the EU Commission’s first antitrust action; let’s skip the fact that terms like “infection” and the liberal use of “commercial” hides the same error already presented in other pearls of legal wisdom already debated here, the reality is that the entire frame of reference is based on an assumption that I heard the first time from a lawyer working for a quite large firm: that since open source software is “free”, companies are entitled to do whatever they want with it.

Of course it’s a simplification – I know many lawyers and paralegals that are incredibly smart (Carlo Piana comes to mind), but to this people I propose the following gedankenexperiment: imagine that within the text of the linked article every mention to “open source” was magically replaced with “proprietary source code”. The federal circuit ruling would more or less stay unmodified, but the comment of the writers would assume quite hysterical properties. Because they would argue that proprietary software is extremely dangerous, because if Microsoft (just as an example) found parts of its source code included inside of another product, they would sue the hell out of the poor developer, that would be unable to use the “Cisco defence”: to claim that Open Source “crept into” its products and thus damages should be minimal. The reality is that the entire article is written with a focus that is non-differentiating: in this sense, there is no difference between OSS and proprietary code. Exactly like for proprietary software, taking open source code without respecting the license is not allowed (the RIAA would say that it is “stealing”, and that the company is a “pirate”).

So, dear customers of White & Case, stay away from open source at all costs – while we will continue to reap its benefits.

See you in Brussels: the European OpenClinica meeting

Posted by cdaffara in OSS business models, OSS data, blog on April 8th, 2009

In a few days, the 14th of April, I will be attending as a panelist the first European OpenClinica meeting, in the “regulatory considerations” panel. It will be a wonderful opportunity to meet all the other OpenClinica users and developers, and in general talk and share experiences. As I will stay there for the evening, I would love to invite all friends and open source enthusiasts that happen to be in Brussels that night for a chat and a Belgian beer.

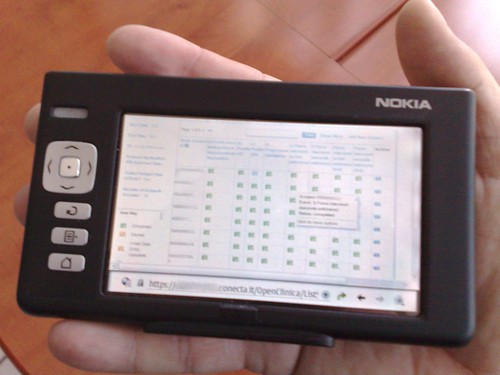

As for those that are not aware of OpenClinica: it is a shining example of open source software for health care; it is a Java-based server system that allows to create secure web forms for clinical data acquisition (and much more). The OpenClinica software platform supports clinical data submission, validation, and annotation; data filtering and extraction, study auditing, de-identification of Protected Health Information (PHI) and much more. It is distributed under the LGPL, and does have some really nice features (like the design of forms using spreadsheets – extremely intuitive).

We have used it in several regional and national trials, and even trialed it as a mobile data acquisition platform.

If you can’t be in Brussels, but are interested in open source health care, check out OpenClinica.